Le rapport final est aussi disponsible en français.

Many people across Canada’s agri-food system passionately believe that the country can generate economic opportunities and deliver societal benefits from aspiring to be the planet’s most trusted and sustainable food leader.[i] Deciding how to achieve this ambition is the issue. Over the past 12 months, Canada 2020 reached out to nearly 600 agri-food stakeholders (see p. 2) to discern what could be done to enable this and why this is so vital. We started with the premise that collectively protecting Canada’s food brand is a conduit to embrace the changes needed to put this vision within reach. Since many ideas shared during our outreach have been well-articulated in other studies, we distilled here what we heard into one over-arching concept and three connected enabling priorities:

A NEW “COMPACT” – based on explicit accountabilities – is required among the agri-food sector, governments (all levels) and adjacent sectors. Food issues are too complex and the opportunity for success is too great to do otherwise. For many, decoupling economics from social and environmental performance is no longer possible or desirable. Validating win-win outcomes is becoming a priority (e.g., by improving soil health even more, agriculture can unleash productivity gains and become a greater carbon-sequestering machine). While the sector is displaying a new collaborative discipline to improve care and sustainability that is pre-competitive[ii] and more accountable, more is expected from industry to improve practices (e.g., on biodiversity) and transparency. The marketplace is signaling to all that ensuring confidence in Canada’s food supply carries new obligations. In return, governments must be more strategic about a supersector that consistently generates jobs and wealth across the country, is a lynchpin for caring for eco-systems and a partner in reducing food insecurity. Governments must be more accountable for ensuring policy coherence across jurisdictions/departments and accelerate regulatory processes to attract and retain investment. Enablers:

1. PEOPLE – Accelerate diversity & systems-thinking [Action: for all]

a) Improving governance and perspectives require association boards and government roundtables to devote 20% of their seats to, e.g., Indigenous, civil society, social scientists, health, environment, investment, technology sectors; producers should be included on processor and retailer boards.

b) Canadian agri-food thought leaders need to be part of global dialogues about transforming the food system (which can influence global standards and goals); e.g., the next emerging issue is “true cost accounting” (i.e., understanding and pricing-in the externalized cost of producing food)

2. METRICS – Leverage stewardship to confer financial & societal benefits [Action: industry led]

a) Industry can leverage value from backing up and stewarding food claims (i.e., safe, sustainable, reliably supplied, nutritious) across every value chain. The metrics gleaned from doing so, often enabled by advanced technologies, is key to boosting on-farm/company productivity and profitability (e.g., optimizing inputs, reducing GHGs) and for creating value-added opportunities and new IP. As a performance-driven and global leading sector, Canada requires a new national data strategy to support such proprietary actions, advance pre-collaborative initiatives and satisfy public reporting.

b) Industry needs to roll up data (above) to link and benchmark responsible practices for investors, the public and for export markets: (1) The wide variety of existing sector sustainability/care programs need a consolidated picture and identify where there are gaps. (2) This is a basis for developing a national index of agri-food performance, verified against globally-accepted ESG principles[iii] with outcome-based targets aligned with the SDGs. Industry to lead this in collaboration with government, NGOs and academia. This tool can also be used to proactively set joint priorities, e.g., with shippers, researchers.

3. POLICY – Ensure predictability & reliability to protect reputation & attract investment in an uncertain global economy [Action: government led]

a) Government needs to build a wider understanding among stakeholders of what science-based regulations means and to assess changing science. In doing so and by recognizing industry progress on ESG (above), accelerating regulatory change and ensuring balanced policy decisions should be justified.

b) Mitigating longer-term trade risk demands a broader view of national interest. Market access is not the only metric of success however appealing in the short-term. As a middle power, a holistic trade strategy can reflect a major advantage: many 21st century global agri-food business risks (climate change) are Canada’s agri-food opportunities. Canada’s food brand can be enhanced by demonstrating how Canada is mitigating such risks and maintaining the right regulatory system. In doing so, government can better position Canada as a safe harbour for agri-food investors.

NEXT STEPS – Based on what Canada 2020 heard, Canada’s food reputation should be a strategic priority. Protecting Canada’s trusted food brand is a catalyst for change but Canada is not the only country seeking to differentiate its food system on the basis of reputation. At the cusp of the next policy agenda, it is up to agri-food stakeholders to decide whether this is important enough to take the necessary steps to, indeed, become one of the world’s most trusted and sustainable food suppliers.

BACKGROUND – By working with its partners, Canada 2020’s dialogues included several labs held across the country since December 2018 and culminated in the National Forum on Agri-Food: Competing in a New World Order on November 6-7, 2019, in Ottawa, where some 40 diverse speakers sparked further discussions. This final report is to be read in conjunction with the Synthesis Report, What We Heard, Dec. 2018 – Sept 2019: Backing-up the Canada food brand to enable the country’s food ambition (cover image) which summarizes the lab dialogues. Agendas and other information on the project is found at: http://canada2020.ca/canadafoodbrand.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS – Canada 2020 thanks its national forum partners: Global Institute for Food Security, Syngenta, Agriculture & Agri-Food Canada, Arrell Food Institute (University of Guelph), Dairy Farmers of Canada, Enterprise Machine Intelligence & Learning Initiative (EMILI), Food & Beverage Canada, Genome Canada, Fisheries Council of Canada, Lakeland College, TrustBIX Inc., and thanks its food lab partners: Arrell Food Institute (University of Guelph), Food & Consumer Products of Canada, Genome Canada, GS1 Canada, National Research Council, Nutrien, Olds College, Protein Industries Canada, Syngenta.

Canada 2020 also appreciates the collaboration with other organizations in holding its food labs, including the Margaret A. Gilliam Institute for Global Food Security (McGill University) and Port of Halifax, and in moderating at the national forum, including: Canada West Foundation, Canadian Agri-Food Policy Institute, Chamber of Digital Commerce Canada, Dalhousie University, Glacier FarmMedia, HEC Montréal, Kitchener-Waterloo Chamber of Commerce/Canadian Chamber of Commerce, Council of the Great Lakes Region, Loblaw Companies Ltd., McConnell Foundation, Scale AI.

The Canada Food Brand Project is led by Canada 2020 Senior Fellow, David McInnes.

This document does not imply endorsement by partners or participants

[i] As informed by The Advisory Council on Economic Growth (2017), Canada’s Economic Strategy Tables: Agri-Food (2018) and the National Food Policy Report (2018).

[ii] Investors are linking long-term yield to a holistic view of risk by assessing environment, social, governance (ESG) factors. SDGs: UN Sustainable Development Goals.

[iii] The Canada 2020 Synthesis Report noted that Canada is a global leader in some areas (e.g., certified sustainable beef; 4-R fertilizer program), is a top-tier performer in others (e.g., pork has the 2nd lowest carbon footprint; food-grade soy traceability; sustainable wild caught seafood) and is conforming to global best practices in others (e.g., certified sustainable canola; horticultural food safety).

Remarks from Michael Wernick to the Canada 2020 4th Annual Indigenous Economic Development Forum

November 27, 2019 (The Westin Ottawa)

Kwe Kwe, Tan’si, Ullakuut, Bouzhou, Bonjour and Good Morning.

Let me also begin by acknowledging that we are gathered on the traditional territories of the Algonquin peoples of this part of Turtle Island, and by thanking Elder Venra who helped us get today’s gathering started in the right way.

I also want to thank Canada 2020 for the invitation to join today’s dialogue, and acknowledge the many wonderful speakers and panellists gathered here today, many of whom I have had the honour to meet along the path I have taken.

The diversity of Canada’s Indigenous peoples, their history and their present realities, is such that it is rare that any statement holds true for all. Rather it is weaving or braiding those diverse experiences and realities together that brings us closer to finding common ground and a way forward. That is the great service Canada 2020 is providing to us today.

All I can offer in the next few minutes is to share, with great humility, some reflections from my own journey, suggest where that common ground may be found, and propose a menu of specific actions that could be taken. My contention is that we have an opportunity right now for a non-partisan agenda that would make a tangible difference.

My own journey with Indigenous issues began in 1985, as the desk officer at the Department of Finance for Indian and Northern Affairs, and for the next 34 years I returned many times to the path of Indigenous issues, always as a servant of the Crown, always in the executive branch of the federal government. Half of my career I worked for red governments and half of it for blue.

Pulling together the biography you have in front of you, that traces my journey it jumped off the page that along the way there were some big setbacks, when exciting breakthroughs stumbled and collapsed at the last step, disappointing not just the government of the day – but also the Indigenous leaders who had taken great risk to work collaboratively rather than sit back and reject.

The 1987 Constitutional Conference chaired by PM Mulroney, the Charlottetown Accord, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples and the Gathering Strength response, the Kelowna Accord, the First Nations Education Act, the First Nations Governance Act. These events have reinforced a view I often heard, and still do, in some circles of punditry and politics that Indigenous issues are intractable, and that the career of every Minister and every National Chief will ultimately end badly.

I reject that view. Along the way there have also been important breakthroughs. The entrenchment of constitutional protections in sections 25 and 35 of our Constitution just one generation ago (I was in the crowd on the Hill that rainy day in April) has changed the power balance and opened up a path that runs not through legislatures but through the courts. More than 20 Supreme Court rulings have established a body of law and principles such as Honour of the Crown, duty to consult, duty to diligently implement, and concepts of Aboriginal title and Metis rights that have real impact. The law has created leverage and opportunity for Indigenous peoples here in Canada that no other Indigenous peoples in settler countries have achieved.

In particular the 26 modern treaties addressing land claims or self government or both have given communities and people meaningful tools to regain a degree of sovereignty and build a better future.

I especially want to lift up the Inuit leaders, past and present, who have built something unique in the world over the past 20 years, and the Yukon First Nations who left the Indian Act and achieved self government a generation ago.

These agreements, as well as dozens of litigation settlements, were in part intended to address some of the most egregious wounds created by our troubled history, which was a key recommendation of the Royal Commission in 1996. In some ways they can never be enough, but by acknowledging and facing up to the past they have allowed at least some healing and freed up energy and effort toward shaping the future. Among them I would note the residential schools settlement and more recent settlements related to childhood experiences, the apologies for forced relocations, the settlements of the Lubicon and Bigstone Cree claims, the creation of the Qalipu First Nation, the Paix des Braves in Quebec.

This is not to overlook the flaws and imperfections in how many of these initiatives have been implemented, or to deny that there is so, so much more left to do.

I do contend they illustrate that with good will, mutual respect and courage, common ground can be found and progress achieved – but also that the quest for the perfect and pure can be the enemy of the good and may needlessly prolong misery.

Each success creates hope and momentum, and concrete lessons that can carry forward to new successes. Emulating and spreading success stories is often the most effective approach to creating positive change in the world.

Our history tells us that there is no reason for Indigenous issues to be caught up in divisive party partisanship. Each of the eight Prime Ministers and ten Ministers I have served – yes I started and ended with a Trudeau – has in his or her own way attempted with personal commitment and at some political cost to tackle the profound challenges of what we now call reconciliation and each has seen achievements and setbacks along the way. I can also say have seen the best and the worst from provincial governments of all stripes, red, blue and orange.

So my assertion is that there is ample room right now for a non-partisan or multi-partisan agenda here in Ottawa, and indeed an urgent need for an intergovernmental agenda bringing together all governments in our federation.

Given the high failure rate of grand scale broad spectrum political initiatives like the Charlottetown and Kelowna Accords, and of some of the more targeted structural reforms, it seems to me that the best approach is one of relentless step by step change, working together, and that a good place to start in 2020 is in fact economic reconciliation.

Whether you come from the red, blue or orange camps in national politics, or from the pragmatist or ideologue camps in Indigenous politics, from the public or private sector, no one wants a future of poverty, unemployment and dependency. There are many good practices and ideas we can quickly build on, especially if we speak directly and honestly with each other.

To paraphrase someone I admire who spoke to Canada 2020 earlier this year – there are no blue ideas or red ideas or orange ideas – just ideas, good and bad.

I don’t think it has anything to do with majority or minority government: many of the big initiatives that failed in the past were initiated by majority governments and some important successes were achieved by minority governments.

I do think it has to do with common ground. I can see at least five areas on which to build.

The first point of common ground should be to say more often to each other that there can be no broad progress in any community anywhere on social, health and justice outcomes if there is no economy. People want a degree of personal autonomy, they want jobs and opportunity to build something for themselves and a future for their families, whether it is a career, a home, a retirement nestegg, or a business.

Communities need an economy that will generate revenues to pay for services and that can be monetized to finance infrastructure. The government in self-government means collecting revenues and accounting for their use, not dependency on transfers.

The second point of common ground, conversely, should be that in 2020 economic growth must be sustainable and must be inclusive. Indigenous peoples knew this before the rest of us began to catch on and catch up. We must ensure economic and infrastructure projects in and near Indigenous communities are held to the highest standards of environmental impact and that these communities are leading, not following, the great energy shift under way.

I would add under the social dimension of sustainability that we must be vigilant not to see the historic inequality between indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians morph into a new form of inequality among Indigenous Canadians.

Third, and this may be contentious for some, we know that economic outcomes are hugely affected by the quality of governance. I am a big fan of the 2012 book Why Nations Fail and the compelling case it makes for inclusive governance. We must chart a course where we do not end up with everyone working for Indigenous governments and their state owned businesses, but nor do we end up with unaccountable oligarchs.

Fourth, the ingredients of activating economic growth and activity are the same for everyone – land and resources, location, access to supply chains and markets, access to start up and patient capital, people and their skills and talents, and a blend of innovation and entrepeneurship. Indigenous economies are not exempt from the principles of economics.

Fifth, there is no single economic growth strategy or toolkit that will work for all Indigenous peoples. We have to be moving on all fronts. There will have to be very specific approaches for Inuit and Metis and we will have to pay much greater attention to the half of Indigenous people who come to study, work and live in non-Indigenous communities but often have profound ties, including voting rights, in their home communities.

The good news is that there is a diversity of opportunity spreading into new sectors and industries – natural resource extraction and processing, ecotourism cultural tourism, cultural creation, clean energy, broadband infrastructure, selling into procurement supply chains, environmental monitoring, air and bus transportation of people, use of drones for surveying or wildlife monitoring, shipping and logistics, introducing airships and hoverbarges to replace failing ice roads, cleaning up orphan wells and contaminated sites, removing old munitions, greening of military bases, building and maintaining housing and community infrastructure, hosting data and server farms in secure locations, selling directly into Amazon and Alibaba.

We know that for many communities despite the opportunities there are all too many obstacles and impediments in the way. Location, scale, lack of capital, lack of skilled labour, lack of reliable infrastructure, lack of broadband – these are still all too common and require focus and effort.

We also know that some key obstacles are created by the unique legal underpinnings of most Indigenous communities. As short as that path would be, and perhaps it is worth a shot, I do not think we will ever see consensus for a simple one page bill that says “the Indian Act, 1951 is repealed, effective five years from Royal Assent”. Because there is not going to be an easy consensus about what will follow, not just in Parliament, but in Indigenous politics. What happens after exit?

Since the big breakthrough in 1982 all of the subsequent constitutional rounds failed. We have only managed two exit strategies to date. One road is the modern treaty. The other is the workarounds that are optional, not mandatory. Many in this room will be familiar with at least one of them (though perhaps by acronym): the First Nations Land Management Act, the First Nations Oil and Gas Act, the First Nations Commercial and Industrial Development Act, the First Nations Fiscal Management Act and its creations the First Nations Tax Commission and the First Nations Financial Authority.

However, If we are candid, most First Nations leaders in fact want to retain three essential legal features of the Indian Act – inalienable communal land, shielding from provincial laws of general application, and exemption from taxation of income earned on reserve.

That is understandable, but it does mean there is no simple version of a successor regime, and it will mean extra work to create winning conditions for economic activity. The good news is that this is quite achievable. I personally think there is a potential third exit strategy – of updating the historic treaties with new constitutionally protected side agreements and implementation agreements – but that is a big topic for another conference another day.

My own view has long been that the way to get rid of the Indian Act is the Jenga strategy – you know the game where you have a pile of logs and you pull one out, the another, then another until eventually the structure just collapses. If we pull more communities out one by one by concluding modern treaties and increasing take up of tools like the First Nations Land Management Act, and if we pull out just a few more pieces of the Indian Act regime, we get closer to the day when it comes crashing down. Perhaps we are closer than we know.

So I want to close by putting forward some very specific initiatives, that would move us forward. My focus is on creating economic activity, and I am setting aside for now some other important aspects of our broader reconciliation journey. I speak for no-one but myself. Here are twelve specific things we can do.

And of course, there are many more pragmatic things that can be done to address access to capital, to build a skilled workforce and to grow more entrepreneurs and business leaders. I can’t touch on them all. You have sone very qualified people coming up later in this conference.

I am quite sure some people may not like some or indeed any of my proposals. Fair enough. Make your own. I know from experience some people will argue I am just making a more comfortable Indian Act and we should wait for a bigger reform – but I would say after nearly seventy years it is time to fix what can be fixed and move on from there.

What I really hope you will take away is a message of optimism and a greater sense of ambition. That there is ample common ground for an agenda of economic reconciliation. That there is no reason for it to be derailed by partisan politics or minority Parliaments.

After 34 years on this road, my core belief is that what we call Indigenous Issues can and will yield to good policy, good governance, and good administration. Relentless pragmatic changes, one step at a time. will take us further along the path to a much brighter future.

People have earned the right to a sense of scepticism. Trust can be difficult to build and is quick to crumble. But pessimism and defeatism It is not what Canada is all about. Not in 2020. Not ever.

Thank you. Merci, Nakurmik. Meegweetch.

Over the course of the final frantic days of the 2019 federal election campaign, more than 200 industry leaders, educators, and policy makers gathered to discuss Canada, Cannabis and the economy at Canada 2020’s Canadian Grown. The pace of development in this sector has been ground-breaking for Canada. Other jurisdictions around the world are now using Canada’s regulatory and economic framework as a model for their industries. Canada and the cannabis industry is disrupting more than policy circles around the G7 and the globe – Canada is creating new jobs, new supply chains and economic opportunity in this burgeoning economy at home. The one year anniversary of recreational cannabis is a good opportunity to review and reflect on what went well and where the opportunities lie. The second year in Canada promises to be just as exciting as the first – Phase II will witness the entry of edible products and other industry product innovations to the Canadian marketplace. Public perception of the industry is generally positive although consumers want to know more about products and economic contribution to the Canadian economy and their local economies.

Canada 2020 in partnership with Genome Canada, hosted Canadian Grown on the one year anniversary of the legalization of cannabis in Canada.

The anniversary afforded the opportunity to gather industry, educators and policy makers alike to the two day event in Toronto, ON. According to Statistics Canada and industry experts at Canadian Grown, it is estimated more than 5.9 million (or 16.7%) Canadians are regular users of recreational cannabis and more than 9,000 Canadians are now directly employed in the sector. This doesn’t include additional economic benefit numbers which trickle down (and up) from the sector. This one year old sector has contributed more than $8.2 billion to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 7 months in 2019.

There is still much work to do in many divergent policy areas. The retail rollout has not been uniform across Canada and this presents challenges of supply, customer access, marketing and advertising, growing capacity and taxation. There remain questions about the future of the medicinal sector and patient care issues. Research, development and intellectual property remain a key focus of industry players as well as recruitment and retention of highly skilled workers. The black market for illegal product and illegal selling activity is also a focus of government and industry.

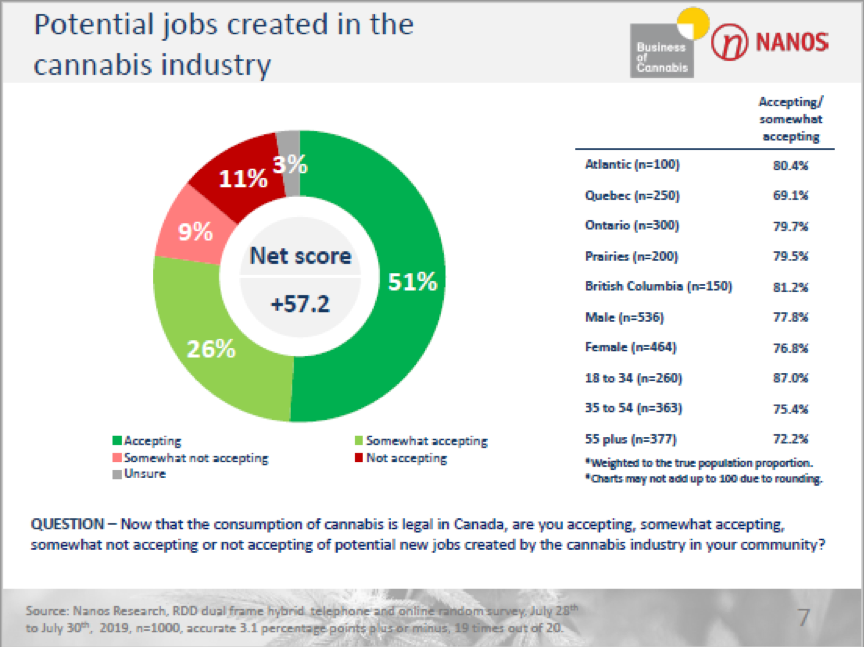

Overall, Canadians have a positive outlook on the some aspects of the industry in most regions of the country. More than 76% of Canadians surveyed by the Globe and Mail’s Report on Cannabis were either accepting or somewhat accepting of potential new jobs created by the industry in their home community. Canada 2020 was pleased to work with Genome Canada to produce this timely and informative industry event. Canada 2020 will be hosting a Policy Lab in the late fall of 2019 to continue the conversation started at this ground breaking event.

Prepared for Canada 2020 by Chris Smillie / Furthermore

The path to recreational cannabis legalization in 2018 was fairly well worn by the medical cannabis regime with roots back to an Ontario Court of Appeal decision in 2000 and two decriminalization attempts in 2003 and 2004 in the House of Commons by successive Prime Ministers. An unscripted political decision made by the newly minted Leader of the Liberal Party Justin Trudeau made in a park in Kelowna, BC in the summer of 2013 ultimately did become the law of land October 17, 2018. Health Canada became the regulator and licensor for the recreational market as the policies, procedures and processes were already functional and sufficiently robust in the medical regime.

The Federal Task Force on Cannabis Legalization and Regulation was struck in mid-2016 by the Prime Minister with a mandate founded on two principles – public health and public safety. These principles were implemented with a view to the long term and did not take into account any functional regulatory thinking on marketing or advertising. The Task force consulted with industry, other jurisdictions and Canadians writ large over a 5 month period. After some consideration there was a conscious choice made to keep the medical and recreational markets separate at the outset of the process.

The Task Force did not address or forecast short or long term economic impact of the industry or take any economic considerations into account. The Task Force operated without the benefit of a breadth of academic research on much of the subject matter as in Canada cannabis was an illegal substance and the country lacked a breadth of clinical information on the substance. Similarly, even as elimination of the illegal market was part of the justification for legalization, the Task Force did not study this issue or make recommendations to stem growth.

The original mandate of the Task Force did not address issues of full amnesty; however the government did implement a pardon regime for Canadians with simple possession convictions with Bill C-93 in early 2019. According to some stakeholders like Cannabis Amnesty and some political leaders, Canada has a record of disproportionate and unfair prosecution and charges on certain populations. Advocacy work for expungement continues as the pardon regime may be inadequate for many Canadians who want to travel, sit on corporate boards as directors or volunteer with children’s organization. Recreational legalization means Canada is also afoul of some international treaties which makes conversations difficult across diplomatic channels but the industry views this as the cost of innovation and economic leadership.

This conference was attended by large Licenced Producers, industry experts/commentators, and some academia and public policy makers. The following are a series of themes and ideas presented at the conference.

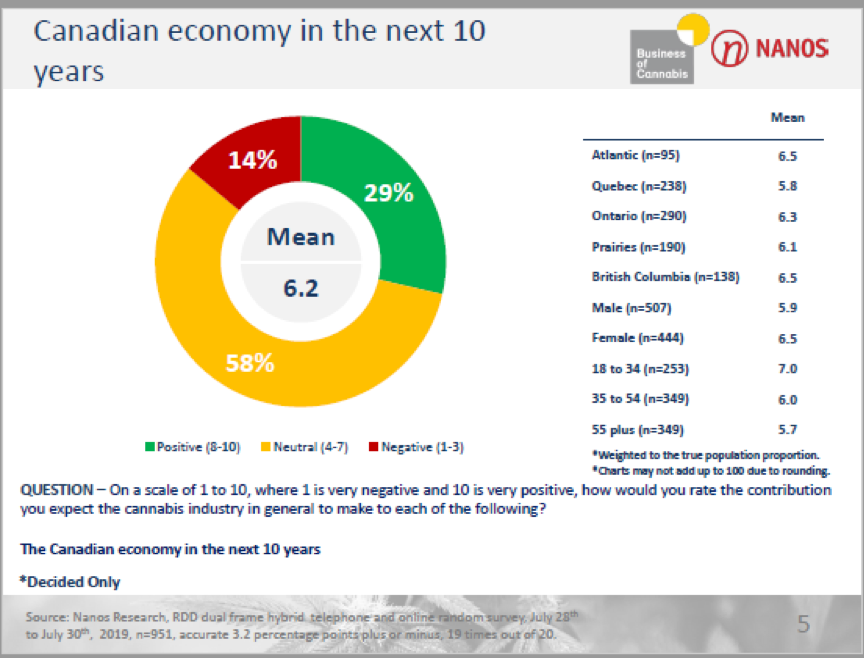

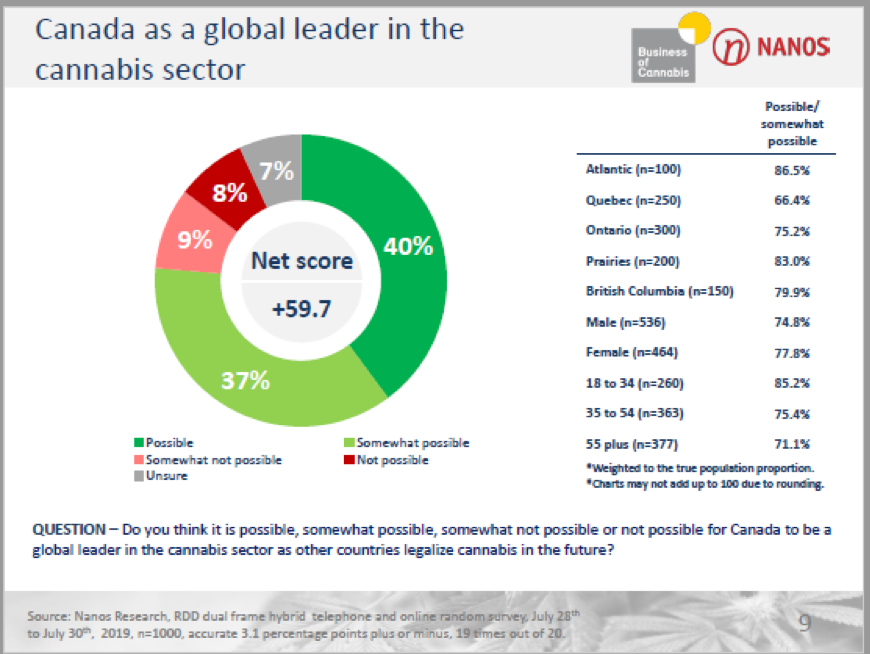

According to data presented in the plenary session, the Canadian public is fairly supportive of legalization, the industry writ large, and potential local jobs associated with this industry. Overall, Canadians have a positive image of the industry and are open to local investment and related job opportunities at home. In addition, Canadians want their local governments to create the conditions for economic success in their local communities. Canadians are not clear on overall economic benefits the industry contributes but are open to learning more about this issue. From the data presented it was evident consumers could be interested in more information on Phase II products. Most regions are positive overall as to Canada’s status as a global leader in the cannabis sector.

Canada has a one year head start on building cannabis industrial infrastructure, raising investor capital and breaking ground in research in this sector. The investing climate is strong in the Canadian cannabis industry because of the first mover advantage. Cannabis investors around the world have flocked to Canada but it is forecasted this could change with more jurisdictions moving towards legalization and liberalization. In addition, the awakening of the US market is going to reshape the capital market landscape and have potential impact on the Canadian industry. Many American states have moved to legalize cannabis in both the recreational and medicinal markets Furthermore, if there is a Democratic administration elected in 2020 in the United States (with a more liberalized approach to cannabis) it could alter financial markets and capital flow globally in the industry.

“Phase II” could further complicate the situation as more finished cannabis products are being brought to market. These products have higher economic production value than Phase I products and thus the economic risk is greater if competing with product from the United States or elsewhere. Investment in manufacturing processes and partnerships with food and beverage companies have increased the stakes in Canada’s industry if first mover advantage is not captured in a reasonable timeframe. Health Canada is responsible for approving Phase II products and that process is underway. The move by the United States to remove “hemp” from the farm bill could be detrimental to the industry in Canada and create greater economic risk for all stakeholders.

Canada’s Cannabis retail landscape is not uniform. Each province has unique rules and regulations concerning consumption age and retail administration. In Ontario, Canada’s largest market by population, there are only two dozen retail outlets and one online retailer. In Alberta, by contrast, there are 65 retail outlets. There were three major threats facing the retail industry identified by various experts at the Canadian Grown event:

In Ontario, municipalities held a vote to participate in or opt out of the retail system and permit potential cannabis retail outlets in their respective jurisdictions. The entire Ontario marketplace is served online by the Ontario Cannabis Store (OCS). Some participants had concerns about licencing and inspection being overly difficult for small industry participants.

Research and Development in the Cannabis sector is in its infancy. Given the complicated nature of Intellectual Property rights in the sector there is natural tension between public and private funding models for research and product development. Process patents for Phase II products will certainly be a growing challenge over the next number of years.

The industry is focused on models of data gathering, plant breeder rights and inherent challenges of dealing in a global IP marketplace. Some members of the audience championed a collaborative approach to patient tracking and IP collaboration. Others championed a model similar to the pharmaceutical industry.

There was consensus amongst some panelists that the challenges associated with the “drug” classification of CBD products were of concern and also Phase 1 products themselves. One LP indicated “regulatory fees” charged by Health Canada as a key irritant for medium and large size LPs and acted as a disincentive to increase product lines for consumers in the short to medium term.

The largest hurdle for the industry identified were filing and approval timelines with regulators for a new product. These act as disincentives for new product applications for consumers.

Some others listed in no particular order but discussed as barriers for R&D:

Cannabis has the potential to play an important role in health care delivery in Canada however introducing a new class of medical treatment into any established system can be disruptive for patients and providers. In addition, the launch of the recreational market is most likely is skewing the true numbers of Canadians whom are seeking cannabis for a medical purpose. The most frequent self-reported reason for self-administration of cannabis are: sleep disturbances, chronic pain, and HIV.

Specialist referral rates are low from General Practitioners for cannabis related care as only a very small number of GPs are actively participating in referring patients to cannabinoid solutions. However, those that are referring patients are doing so very often. The Canadian Medical Association is urging a public health approach and increased reviews for efficacy, safety and quality on CBD products making a health claim.

Will the recreational marketplace displace the medical cannabis regime? The medical cannabis regime is currently in a five year review period. In four years the merits of the system will be examined and a determination will be made as to the viability of the medical system. This was a topic of concern for those on the panel and no consensus was reached. The provision of medical advice is a key element for the care and well -being of Canadians. Dosing issues and interaction(s) with other medications patients may consume at the same time as cannabis are of key concern to the medical and patient community.

Canada 2020 is pleased to host a one day policy lab in the late fall of 2019. More details to follow.

Canada 2020, “Canadian Grown Conference proceedings and program”

Canadian Medical Association “Cannabis Fact Sheet”

Globe and Mail Report on Cannabis, “Nanos Research, RDD dual frame hybrid telephone and online random survey, July 28th to July 30th, 2019, n=1000, accurate 3.1 percentage points plus or minus, 19 times out of 20”

Government of Canada, “Federal Task Force on Cannabis Legalization and Regulation”

Statistics Canada, “Cannabis Stats Hub”

On this election campaign special, we discuss one of Canada’s closest races ever – and what you should expect in the days, weeks, and months to come.

For episode 5 of Open to Debate, David Moscrop talks with Shannon Proudfoot, a journalist with Maclean’s, about the performances of each party so far, minority and majority parliaments, voter turnout, and some ridings to watch.

On September 12, 2019, Canada 2020 held a public event to discuss the challenges facing Canadians ahead of the 2019 federal election. In this episode, you’ll hear a panel discussion covering the issue of foreign interference, and the threat it poses to Canada. Panelists include Richard Fadden, former National Security Advisor to the Prime Minister of Canada, former Deputy Minister of National Defence and former Director of CSIS, and Fen Hampson, Director of Global Security Research at the Centre for International Governance Innovation and Co-Director of the Global Commission on Internet Governance.