Introduction: Trust in Government

A long list of polls and studies tells us that people are turning away from politics and that public trust in politicians has plummeted, but do we know why or how to fix it?

When people watch newscasts or check out political debate online, what do they actually see or hear about politics? Increasingly, it is little more than the shrill and hyper-partisan tone of the “constant campaign,” from cynical negative ads to the barrage of talking points and political spin.

Nor is it clear how or why important policy decisions are made. Too often, they emerge from a black hole or reflect short-term political gain, rather than the public interest. Looked at through this lens, it is not hard to see why people are questioning what politics has to offer them.

This disconnect between citizens and politics appears to be part of a long-term trend that may be reaching a critical point, as the following slide by Frank Graves from Ekos Research suggests:

The blue and green lines show a stunning drop in the number of Canadians and Americans who trust their national governments to do what is right. According to these figures, over the last 50 years trust has plummeted from a high of about 78% into the low twenties here in Canada and the teens in the US.

If accurate, we think this should be of deep concern to the policy community. In a democracy, the legitimacy of governments arises from citizens’ participation in the democratic process, especially elections. A collapse in public trust is likely to be followed by a collapse in participation; and that, in turn, means loss of legitimacy. There are worrying signs that this is already happening: voter turnout is falling, especially among youth; and, as Graves and others have been warning, public trust appears to be tumbling.

We think this trend is connected to two others that have unfolded over the same time period: globalization and the digital revolution. Together, these two forces have transformed our world, making it far more fast-moving and interconnected.

As a result, events and trends are increasingly difficult to predict and manage. Big shifts can happen with little or no notice, such as the terrorist attacks of 9/11, the financial crisis of 2008, or the collapse of oil prices in 2014.

Nor is anyone sure how such events—or our responses to them—will impact on other systems and trends. But if we have learned anything in recent years, it is that, in an interconnected world, they will.

So the speed of change, the interconnectedness of events, and a general volatility around public affairs are defining features of the contemporary world. Making and implementing decisions in this environment requires new ways of gauging public support and establishing legitimacy. The less engaged or trusting citizens are, the more difficult this becomes for governments.

Rebuilding public trust and reengaging citizens should be one of a government’s highest priorities. We believe that Open Government is the way forward on this. It sets new standards for governance that will put an end to many of the cynical or outdated practices and establish new ones that are far better suited to our needs and to citizens’ expectations.

This paper sketches the way forward for a new Parliament after the next election. It begins with an overview of Open Government and explains our reasons for focusing in on one key aspect of it: Open Dialogue. The Open Dialogue Initiative we propose provides a compact and cost-effective plan to build a new capacity for Open Dialogue in Parliament and across the public service, as quickly as possible. This, in turn, will ensure that a government that wants to pursue Open Government after the next election will have a plan that is fully formed and robust enough to make a major contribution to reengaging citizens and rebuilding trust.

2. What is Open Government?

The Open Government Partnership is an international movement of some 65 countries who have joined together to promote better governance through the innovative use of digital tools and a deeper commitment to transparency, openness and public engagement.

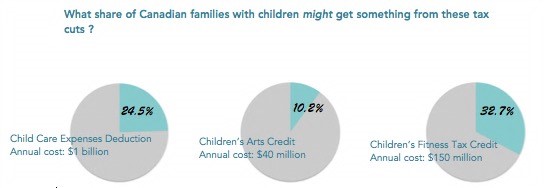

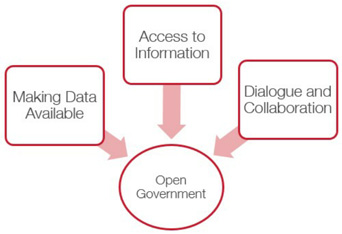

The Government of Canada joined the partnership in 2012 and in its initial Action Plan identified three streams of activity: Open Data, Open Information, and Open Dialogue. Open Data calls on departments to make their data holdings available to the public to use to develop new knowledge products, support more evidence-based decision-making, and make government more transparent.

Open Information calls on departments to advance freedom of information. Lastly, Open Dialogue recognizes the need to engage the public more directly in the policy process. Open Government results from the convergence of these three streams, as follows:

“Openness” is not a new concept. Citizens have always needed information to hold government to account and to make informed decisions. However, Open Government is taking this to a new level.

In 2014, a second Government of Canada Action Plan recognized the principle of “Open by Default” as the basis for these three streams. This implies that government information and data should be available to the public by default. When information is withheld, the onus should be on government to explain why.

If fully implemented, we think the principle of Open by Default would be transformative. It implies nothing less than a reversal of the culture of secrecy and control that surrounds governments. And this, we think, is the key to renewing government for the digital age. While there is a long way to go, the principle has now been officially recognized and adopted by the Government of Canada. The challenge for a new government will be to implement it.

3. Focusing on Open Dialogue

Much of the progress so far on Open Government has focused on Open Data. Many government data sets are in a format that allows them to be shared easily and their content is relatively uncontroversial, so observing the principle of Open by Default requires little change to the culture of government and, from a political viewpoint, is largely risk-free.

The Government of Canada currently has a fairly ambitious plan to advance Open Data and officials are hard at work on it. While adjustments to the program might be needed, a government that wanted to pursue a comprehensive Open Government would not need to reinvent it.

Open Information is more challenging. Documents that contain policy advice, program performance assessments or information on the state of the government’s finances are usually treated as confidential and released only when a government feels ready to do so. Declaring that they should be freely available to citizens—Open by Default—would require a major reversal of the culture of secrecy that now dominates the federal government.

Nevertheless, Freedom of Information has a long history in Canada and elsewhere and has provided policymakers with lots of experience, so the risks are well known. The question for a post-election government is mainly one of leadership: will a new government be willing to take this step?

For at least one party, the Liberals, the decision to move forward on freedom as already been made. Justin Trudeau’s Private Member’s Bill outlines a plan to renew Canada’s 1983 Access to Information Act based on the principle of Open by Default. As a result, all kinds of confidential information and documents would become accessible to the public.

Of the three streams, Open Dialogue is the least well understood and for many politicians and officials, the most worrying. They fear that it could turn over control of the policy agenda to interest groups, saddle ministers with bad decisions or degenerate into a free-for-all that paralyzes decision-making. Such concerns leave them wondering about the upside of Open Dialogue.

In our view, many of the concerns over Open Dialogue are either unfounded or relatively easily mitigated. We also see Open Dialogue as vital to the success of Open Government. Open Data and Open Information are not enough to prepare government for the digital age. As noted, policymaking today occurs in a highly interdependent, fast-moving and volatile environment, often involving many stakeholders. In this environment, dialogue processes can make a major contribution to policymaking in two basic ways:

- They can help ensure legitimacy through key “process values,” such as transparency, responsiveness and inclusiveness.

- They can increase effectiveness by bringing the right mix of people, skills and resources into the policy process to ensure the best decisions are made and implemented.

But to achieve this, the processes must be well designed and well executed—something the current Conservative government has shown little interest in exploring or improving. It has been unwilling to invest time or political capital in building the capacity or skills needed for Open Dialogue. In most departments, traditional consultation (see below) remains the standard approach.

Indeed, what the government often refers to as “consultation” is barely even that. Often, it is little more than an “information session,” where the government announces its plans, provides limited information about them and minimal opportunity for feedback, and then pushes ahead regardless of what others say.

We think this refusal to listen and respond to public concerns is a major contributor to the falling levels of public trust, as well as to a deeply worrying trend in which public policy increasingly conflicts with expert opinion and/or lived experience. As a result, Ottawa is falling further and further behind other national (and provincial) governments, such as the United Kingdom, which has made itself an international leader and trend-setter on Open Dialogue.

Given the Conservatives’ refusal to allow the public service to experiment and evolve, a different government in Ottawa would find that within the public service the pressure to advance Open Dialogue has been building for some time. A new government must be ready with a plan that can address this deficit quickly, while ensuring the job gets done properly.

The Open Dialogue Initiative, to which we now turn, is designed to ensure that genuine capacity-building on Open Dialogue occurs within the federal public service as quickly as possible, but in a discipline way; and that the learning, skills, relationships and culture-change that result become institutionalized and are shared with the broader public policy community.

4. Objectives for the Open Dialogue Initiative

The Open Dialogue Initiative has five key objectives:

Make Open Government the standard for the digital age

Through the principle of Open by Default, Open Government sets new standards for governance in the digital age. The Open Dialogue Initiative will establish Open Government as the “brand” for improving governance in the Government of Canada and introduce the Canadian public policy community to the key ideas behind it.

Establish Open Dialogue as the indispensable third stream of Open Government

The Initiative will examine, test, document and demonstrate the critical contribution Open Dialogue makes to Open Government; and, in particular, to reengaging citizens and rebuilding public trust.

Ensure that Open Dialogue is guided by a principled policy framework

The Initiative will produce a comprehensive policy framework to guide Parliamentarians and officials in designing and delivering effective Open Dialogue processes at the federal level.

Assess how digital tools can be used to support and strengthen Open Dialogue processes

The Initiative will explore the contribution digital tools can make to Open Dialogue. How effective are they at overcoming distance and including large numbers of people? Can they support genuinely deliberative discussions? Are there new tools or techniques on the horizon that might prove to be “game-changers”?

Build a group of Open Dialogue champions who will foster further experimentation and culture-change within Parliament and the Government of Canada

The Initiative will build a group of Open Dialogue champions at both the political and public service levels, who will be informed, experienced and able to speak authoritatively about Open Dialogue processes and their role in the future of governance.

5. Towards an Open Dialogue Framework

A key objective of the proposed Open Dialogue Initiative is to develop a principled policy framework to guide the development of Open Dialogue processes. In fact, much work has already been done on the foundations of such a framework and, based on this, we believe the Open Dialogue Framework should rest on four distinct kinds of dialogue processes:

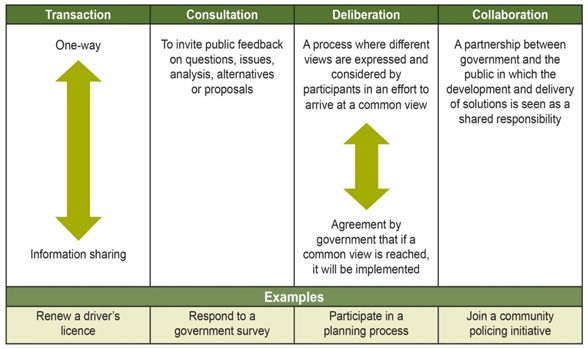

Transactions

A transaction is a one-way relationship in which government delivers something to the public. This could be information, but it could also be a form of permission (licence), an object (drugs) or a service (policing). Transactions thus include not only information exchanges, but also the delivery of many public services.

Consultation

Consultation provides members of the public with an opportunity to present their views on a subject to public officials. The process ensures they have a chance to make their views known to government. Once they have done so, the officials retreat behind closed doors to review the arguments, weigh evidence, set priorities, make compromises and propose solutions. Their conclusions are then presented to the government, which makes the final decisions.

Deliberation

Deliberation allows participants to express their views, but it also asks them to engage one another (and possibly government) in the search for common ground. Whereas consultation assigns the task of weighing evidence, setting priorities, making compromises and proposing solutions to officials, Deliberation brings the participants into this process.1

Collaboration

Collaboration involves sharing responsibility for the development of solutions AND the delivery or implementation of those solutions. A government shares these responsibilities when it agrees to act as an equal partner with citizens and/or stakeholders to form and deliver a joint plan to solve and issue or advance a goal.

Open Dialogue makes appropriate use of all four types of processes. At present, policymakers in the federal government tend to reply on just two approaches—information sharing (transactions) and consultation—for almost every issue. Too often, this results in a mismatch of processes and issues that leads to solutions that are ineffective, difficult to implement or that lack buy-in from citizens and stakeholders.

The motivating idea behind the Open Dialogue Framework is simply that different kinds of issues should be approached differently. The Framework is supposed to help officials choose the right kind of process for the issue at hand.

However, if Open Dialogue rests on recognition of these four generic types of processes, we should not lose sight of the fact that every government is different. The challenge in developing an Open Dialogue Framework is not just to identify the four types and provide criteria to match them with the right kinds of issues. It is also to provide guidance on how to design processes that incorporate or respect the special or unique characteristics of the community in question.

The Open Dialogue Initiative would use the demonstration projects to produce a “made in Canada” approach to Open Dialogue that is appropriate for the Government of Canada. For example, the new Framework would recognize and incorporate our commitment to federalism, the historical place of aboriginal peoples, and the role of official languages.

6. The Project: Who are we engaging?

The Open Dialogue Initiative that we are proposing includes two distinct but complementary streams of activity: the Public Service Stream and the Parliamentary Stream. The former focuses on how Open Dialogue would transform the work of ministers and the public service; the latter on how it would make the work of Parliament and parliamentarians more meaningful.

The public service stream would include five major demonstration projects from five departments (a single project could involve multiple departments), and the parliamentary stream would include three to five projects from the House of Commons, possibly including the Senate. The two streams would proceed in parallel.

A. Open Dialogue Initiative: The Public Service Stream

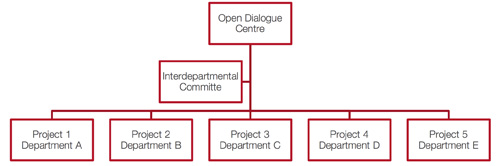

The Public Service Stream would be led by a new Open Dialogue Centre in the Treasury Board Secretariat. The Centre would scout out departments that were planning to launch a significant consultation initiative on an issue and then hold meetings with the officials from that department.

Through these meetings, the Centre would be looking for consultation processes that were also good candidates to be transformed into deliberative or collaborative processes. The Centre would discuss this with departmental staff. If the prospects were promising, staff, in turn, would discuss this with the minister.

The Centre’s goal would be to identify five promising projects from various policy areas that could be completed within 18 months or less. Following discussions with the minister and his officials, the Centre would invite those five departments to participate in the Open Dialogue Initiative by redesigning their consultation processes as deliberative or collaborative ones and then allowing them to be used as demonstration projects for ODI.

Each demonstration project would still be planned, managed and executed by officials from the sponsoring department. However, the Centre would also strike and chair an interdepartmental committee, with representation from each of the departmental project teams. This committee would provide advice and oversight to all of the departmental teams to help ensure that the five projects conformed to basic principles and best practices of Open Dialogue.

The committee would also be responsible for consolidating learning from the projects and producing the new Open Dialogue Policy Framework for TBS. This would eventually become the official policy framework of the Government of Canada for Open Dialogue.

In addition, the Centre would be responsible to inform and engage the public service and the broader public policy community on the progress of the projects. It would also work with the Canada School of Public Service to develop a training program and materials based on the projects.

The Open Dialogue Initiative would conclude with a national conference to educate the public service, MPs, the broader public policy community, and governments across the country on the merits of Open Dialogue and to showcase the results of the project.

Finally, development and execution of the five projects should require few new resources. The principal cost would lie in executing the demonstration projects. However, as each one would be a process that the sponsoring department had already planned to carry out, resources would have been allocated to the project through departmental budgets. In this way, ODC would leverage existing resources and commitments to carry out the work to produce the new framework.

B. Open Dialogue Initiative: The Parliamentary Stream

Many MPs today feel removed from decision-making, which increasingly is vested in the executive, in party leadership and, at times, among political staff.

The Parliamentary Stream of the Open Dialogue Initiative would provide an opportunity to change this by striking special committees of MPs and assigning them the responsibility of leading an Open Dialogue project.

First, House Leaders would meet to identify a list of multiparty issues that could be the focus of such a dialogue. A “multiparty issue” is one that transcends partisan lines enough that members of a special committee could reasonably be expected to work collaboratively. House Leaders would then agree to strike three to five special committees, each with a mandate to use Open Dialogue to find solutions to their respective issues.

A committee’s mandate would charge its members with leading either a deliberative or collaborative discussion aimed at producing a consensus report. House Leaders would agree to a hands-off approach, as long as a committee continued to work within the boundaries and parameters defined by its mandate.

The committees would contain equal representation from each of the official parties in Parliament. Committee members would agree to engage in a non-partisan dialogue and, where the public was involved, to play a new kind of “facilitative” role through the committee.

In our view, the Library of Parliament is well positioned to assume a new and important role in helping Parliament build capacity and carry out successful engagement processes. Its value here was clearly demonstrated in a 2002/3 study on CPP (Disability), when it provided special support to the Sub-Committee on the Status of Persons with Disability.

The government would make a meaningful commitment to act on consensus recommendations, as long as they remained within the boundaries of the mandate and met any special conditions set out there, such as guidelines on recommendation that involve spending.

Should the committee members fail to reach consensus on their recommendations or reach beyond the committee’s mandate, the government’s commitment to act on the recommendations would be invalidated.

C. Realigning Parliament and the Executive

In the final stage of the Open Dialogue Initiative, The Open Dialogue Centre would convene a meeting with members of the parliamentary committees, ministers responsible for the demonstration projects and their senior officials, and representation from the Prime Minister’s Office. Together, the group would discuss the lessons from these exercises for how Open Dialogue could be used to help realign the relationship between Parliament and the Executive.

D. Deliverables

The following is a list of the principal deliverables from the Open Dialogue Initiative:

- Establishment of the Open Dialogue Centre in TBS

- Completion of five Open Dialogue projects in five departments, involving stakeholders and/or individual citizens

- Completion of three to five all-party Open Dialogue projects in the House of Commons, possibly including the Senate

- Completion of an Open Dialogue Framework that establishes an official approach to Open Dialogue for the Government of Canada

- Development of a suite of public engagement learning tools to help build capacity in the Public Service of Canada

- Establishment of a community of articulate and experienced champions for Open Dialogue

- Review of the lessons for realigning the relationship between the Executive and Parliament

7. Conclusion: Back to Public Trust

Since the beginning, modern governments have relied almost exclusively on two basic processes to involve citizens and stakeholders in the policy process; what in the framework above we called information sessions (transactions) and consultation.

But if the engagement approach hasn’t changed much in 200 years, the policy environment has. Citizens today are far less willing than their grandparents to allow governments simply to make decisions on issues of the day. They often want a say on issues that matter to them and they regard this as their democratic right.

Further, globalization and the digital revolution have transformed our world. Issues, events and organizations are often so interconnected that governments are unable to determine how the different options are likely to impact on the environment. To find the fairest and most effective solutions they must engage citizens and/or stakeholders in their deliberations, as they are often far better positioned than government to assess how a policy will impact on them.

Finally, good policymaking often requires more than public involvement to identify solutions. It also requires public involvement to implement them. Community health is an obvious example. Citizens may come together to discuss and develop a promising community health plan, but unless they also commit to acting on it little progress will be made. Engaging them in the deliberations that forge the plan is not enough. The process must go a step further and also secure a commitment from them to help deliver it—and that is a different discussion.

We believe that building the capacity for a more ambitious use of Open Dialogue processes to address issues like this would greatly enhance both the legitimacy and effectiveness of government decision-making.

Our goal is to ensure that democracy continues to work between elections; that citizens and organizations can meaningfully engage with government and Parliament to help shape the direction of a government after it has been sworn in.

As we plan for the next 150 years of Canada, we should be putting in place the processes and institutions that will assure Canadians there are better ways to participate in the policy process than yelling at their televisions or, worse, just turning them off. Meaningful participation should be palpable and therapeutic. Open Dialogue would be an effective antidote to the cynicism that is infecting our democratic institutions.

And this, in turn, would go a long way toward the essential task of rebuilding public trust.