Tweet

Many, many years ago, I was a smoker. When I decided to quit, I told my friends and family and I think that made it a little easier to stick to my own plan.

I think, in theory, balanced budget legislation might be a bit like that – a commitment device. Having made a public statement, governments might feel more committed and follow-through on difficult choices to avoid unnecessary deficits.

In practice, it doesn’t seem to work out that way.

The research finds that balanced budget legislation needs political will to have any effect and if you have that political will, then you don’t really need the legislation.

A look through the last decade of federal and provincial budgets reveals that balanced budget legislation doesn’t predict more balanced budgets. Jurisdictions with a balanced budget law balanced the books in 5 of the 10 years. But so did jurisdictions without such a law.

If balanced budget laws don’t necessarily have the desired positive effects, is it possible they can also encourage governments to do sub-optimal things just to show a $0 deficit?

Models of government behavior say that they will feel pressure to spend public money to keep stakeholders [read: voters] happy. Also, they want to be seen to be busy doing things in office. Governments need stuff to announce: There are pressers to be organized! Talking points to be read! Photo ops to Instagram and Periscope! So what is a government, under political pressure to spend but also under pressure to not be seen to be spending, to do?

Cutting taxes one shiny credit at time

Boutique tax credits start to look pretty attractive, especially the non-refundable ones (the ones that don’t result in a cash payment back for lower income taxpayers). These are credits that can be announced, often in a budget, and re-cycled again, and again. They can be targeted to certain taxpayers based on behavior—for example taking public transit, enrolling in higher education or paying for organized sports for a child.

Administratively, it’s possible to make these credits conditional on some taxpayer characteristics, but not usually income. Instead, boutique tax credits have a veneer of universality–as long as we all fill out the same tax form, we all have equal opportunity to use them, no matter what we earn, right? So when government announces these credits, it’s easy to imagine that many Canadians could benefit.

Better still, if you’re inclined to spend without being seen to do so, after they are announced, these credits just kind of fade into the wallpaper. Remember the Children’s Arts Credit from Budget 2011? How much will it cost (in foregone income taxes) for the coming fiscal year? You probably won’t find that number in the 2015 Budget. Like so many individual tax credits from budgets past, the Children’s Arts Credit is now just part of the fiscal backdrop.

The 2015 Budget documents and communications materials give the current federal government’s retrospective on its own tax cuts, pausing to illustrate how much less folks like “Henry and Cathy” (at $120,000 in family income) pay in taxes since 2006.

Let’s set aside the fact that the budget document claimed that the reduction from 16% to 15% of the lowest personal income tax rate took place in 2006 (and not in fact 2005), and instead let’s look at the other personal income tax reductions listed: the Children’s Fitness Tax Credit, the Children’s Arts Credit, the Public Transit Tax Credit and the Canada Employment Credit to name a few. There’s no special credit for “Matthew’s” yellow lunch box, not yet anyway.

The list is long enough to sound quite impressive. But do these credits represent good tax policy?

Do they use public funds prudently? Reductions in federal revenues have to be made up elsewhere or else they ultimately result in spending cuts, or deficits, or even both.

Do these credits have the desired policy impacts–for example encouraging more physical activity among children? The available research seems to suggest they do not.

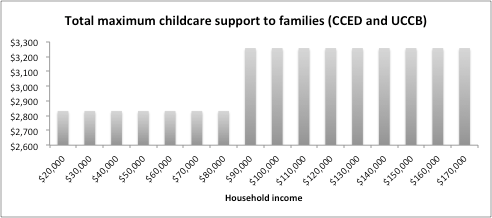

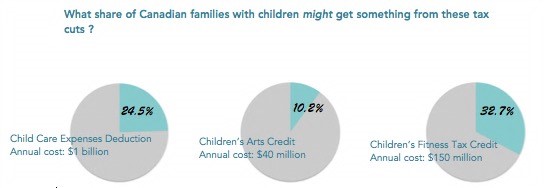

Who benefits most from these boutique credits? Well, not every family with one or more children. Using the government’s own numbers, only up to a third of families are expected to get anything at all from many of these targeted tax cuts:1

The same is true of the much-discussed Family Tax Cut that will only reach, at most, 12.9% of all Canadian households and a maximum of one third of families with children. Bear in mind the above estimates are optimistic and include any family that gets even $1 of federal tax reduction.

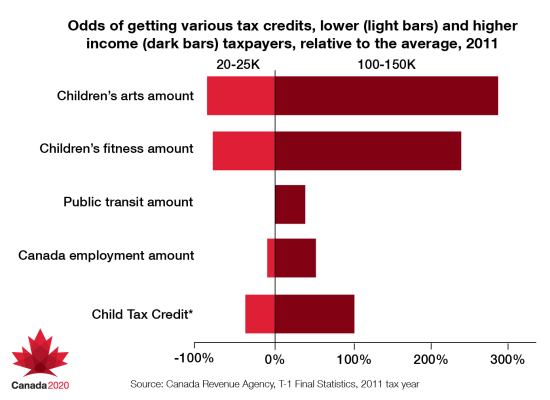

So, while the rules for each of the boutique credits are silent on how much money a taxpayer has to have to benefit, it so happens that wealthier tax payers are more likely to claim these credits. Using the most recent published data on tax returns, here’s what we know about the likelihood of getting some of these boutique credits:2

The dollar value to an individual taxpayer of many of these credits is often very small–just $75 for the Children’s Arts Credit, for example. But, when stacked on top of each other (which is more likely for upper-income taxpayers), they seem to add up. Is this making a difference in what taxpayers are paying and, if so, who’s getting what?

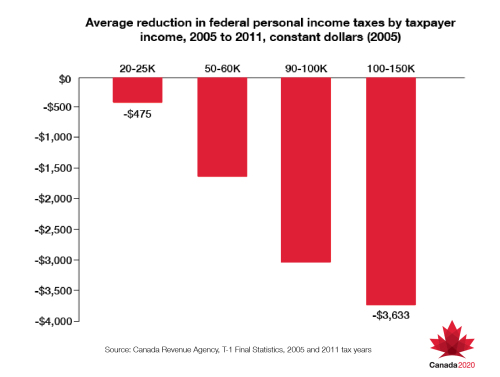

Let’s compare the taxes paid in 2005 and the most recent year available–2011 for modest and upper-income taxpayers.3 Remember, the federal personal income tax rates and brackets haven’t changed. The main personal income changes have been through boutique credits.

In 2011, the average taxpayer with an income between $100,000 and $150,000 paid $3,633 less in taxes. The average taxpayer with a very modest income of between $20,000 and $25,000 saw only $475 back in the same period. These numbers are before the impact of the new Family Tax Cut and the doubling of the Child Fitness Tax Credit – both of which are likely to accelerate the same trend.

Final Thoughts

In some cases, there can be good policy reasons to try to reward taxpayers with credits for doing certain things. But those choices need to be transparent about who wins and how the fiscal room will be adapted.

When public commitments to show balanced books are given precedent over promoting economic growth, boutique credits may become nearly irresistible. These trinkets are easy to make but then become hard to see.

During the 1960s and 70s, personal income taxes only brought in 30-40% of all federal revenues. Today we’re trending closer to 50%. If a government is going to bind itself with public commitments to balance spending with revenues, it had better make sure that its main revenue stream is sustainable.

Sneaking around to hide an addiction to shiny but regressive credits is just a spending habit by another name.

Tweet