Dear Prime Minister,

Congratulations on your election (or re-election). You deserve a rest, but regrettably you will not get one, because now you must govern. During the campaign, your attention was focused on the daily battle for votes, but now the future stretches before you. Your most important task—like that of all your predecessors—is to create the conditions in which Canadians and Canada can thrive, now and in the years to come.

Doing so, however, requires a measure of foresight. Wayne Gretzky’s hockey adage—that you need to skate to where the puck is going to be, not where it has been—has become something of a cliché, but it is an apt description of the policy challenge you face.

Today, this challenge is particularly important, and difficult, in relation to foreign policy, because the world is changing so quickly. New powers are rising. Competition for markets, energy and resources is intensifying. Digital technologies are revolutionizing how we work, communicate and collaborate, but also raising new concerns about intrusive surveillance, cyber-attacks and violent radicalization across borders. Millions of people around the world are entering the global middle class for the first time, but other societies remain mired in cycles of poverty, poor governance and conflict. Meanwhile, evidence of climate change and its damaging effects continues to mount. Confronted with these and other challenges, the system of global institutions and rules is under growing strain.

These changes matter for Canada and for our future. They matter, in part, because Canadians have long believed that their country should play a constructive role in addressing global problems; we are not isolationists. They also matter because these changes have potentially serious implications for the prosperity, security and well-being of Canadians. If you, Prime Minister, fail to maintain Canada’s competitiveness, or to address transnational threats to our security, or to deal with pressing environmental problems, we will all end up worse off.

For Canada to succeed—not in the world we have known, but in the world that is emerging—you will need to pursue a forward-looking foreign policy. The starting point for such a policy is a simple, but powerful, principle: that Canada’s interests are served by working constructively with others. This principle was at the core of Canada’s largely non-partisan foreign policy for the better part of six decades following World War Two. Its most successful practitioner in recent decades was a (Progressive) Conservative prime minister, Brian Mulroney, who invested in diplomacy and the military while championing Canada’s role in the United Nations, among other things.

This emphasis on constructive diplomacy never prevented Ottawa from taking strong stands on important issues, from nuclear arms control to South African apartheid. Nor did it preclude participation in close military alliances, including the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

Effective multilateralism strengthened Canada’s relationship with its most important partner, the United States—a relationship that Ottawa, completing the circle, parlayed into influence with other countries and multilateral institutions.

In recent years, however, our relations have weakened. Tactless attempts to pressure the White House into approving the Keystone XL pipeline, for example, have placed new strains on the Canada-U.S. relationship. Without high-level political support from Barack Obama’s administration, progress on reducing impediments to the flow of people and goods across the Canada-U.S. border—a vital Canadian interest—has flagged.

Canada’s standing in many multilateral bodies, including the United Nations, has also diminished. We became the only country in the world to withdraw from the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, undoubtedly irritating Berlin on the eve of Germany’s hosting a major meeting on the issue. Ottawa also cut off funding to the Commonwealth Secretariat and boycotted its last meeting in protest against the host, Sri Lanka, even though other countries, such as Britain, were equally critical of Sri Lanka, but decided to attend. While we used to be a leader in multilateral arms control, now we are laggards—the only member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization that still has not signed the Arms Trade Treaty on conventional weapons.

Rather than maintaining the virtuous circle of effective bilateral and multilateral diplomacy, Canada has been marginalizing itself. It is one thing to excoriate our adversaries, as we have recently taken to doing, but carelessly alienating our friends and disconnecting ourselves from international discussions is simply self-defeating. Canada is not powerful enough to dictate to others, even if we wished to do so. We have succeeded in international affairs by building bridges, not burning them.

This point seems to be lost on some foreign policy commentators, including Derek Burney and Fen Hampson, who disparage this approach as “Canada’s Boy Scout vocation,” or a kind of woolly-minded idealism. Their scorn is misplaced. Building international partnerships, including through energetic and constructive multilateral diplomacy, is a necessary condition for advancing Canada’s interests. Nothing could be more hard-headed.

Your challenge, Prime Minister, is to devise a foreign policy that reaffirms this approach while responding to the sweeping changes taking place in the world: a foreign policy for the future. Allow me to offer the following suggestions—on our relations with Asia and the United States, our policy on energy and the environment, and our approach to fragile states.

A forward-looking policy would, first, recognize that the centre of economic power in the world is shifting with unprecedented speed away from the advanced industrialized countries and toward emerging markets, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region. In 1980, for example, Chinese economic output was just a tenth of the U.S. figure, but by 2020 it is expected to be 20 percent larger than that of the United States. Despite a recent slowdown, growth rates in emerging economies are expected to continue outperforming those of the advanced economies by a wide margin.

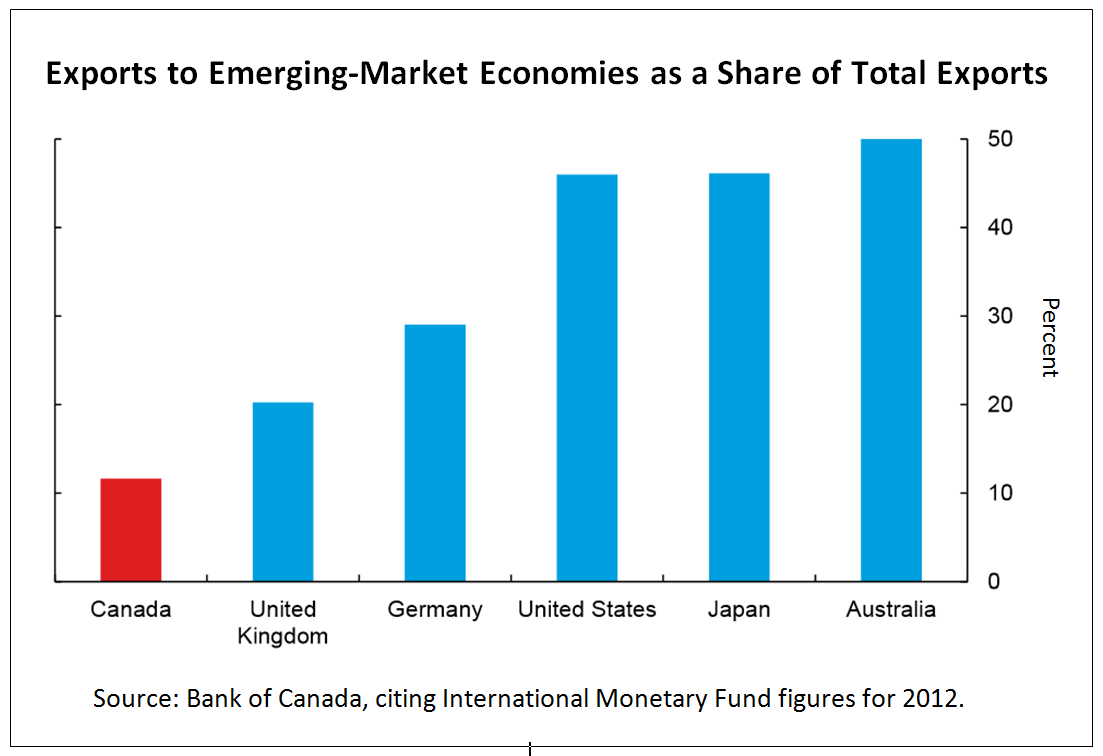

Deepening Canada’s economic links with these emerging powerhouses would allow us to benefit more from their elevated rates of economic growth, but we have been very slow to do so. Fully 85 percent of our exports still go to slow-growth advanced countries, according to figures cited by the Bank of Canada. The recently finalized trade deal with Korea was a step in the right direction, but we still lag far behind our competitors (see figure). Canada’s market share of China’s imports, for instance, did not increase between 2004 and 2013, and our share of India’s imports actually fell during this period.

This is not only bad for Canada’s long-term growth prospects; it also imposes costs today. A small but telling example: Australia’s recently concluded free trade agreement with China eliminated tariffs on Australian barley imports into China, among other things. Selling food to the Middle Kingdom is big business—and an enormous opportunity for Canadian exporters. Now, however, Australian barley exports to China will enjoy a $10 per tonne advantage over Canadian barley. We lose.

The good news is that Canada is participating in negotiations for a Trans-Pacific Partnership, an economic cooperation zone that will, if completed, encompass twelve countries including Canada. In addition to pressing for a successful conclusion of these negotiations, you should initiate free trade negotiations with China, which is not part of the TPP, and with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, while expeditiously concluding Canada’s ongoing bilateral negotiations with India and Japan.

Even these steps are only a beginning. Trade deals can secure market access, but business relationships in Asia are often founded on personal contacts and familiarity. Canada still has a lot of work to do on this front, too. Other western countries recognized Asia’s potential years ago and launched concerted strategies to strengthen their professional, cultural and educational links with the region. In 2009, for instance, President Barack Obama announced that the U.S. would send 100,000 American students to study in China by the end of 2014. (The target was met and surpassed last year.) Australia’s New Colombo Plan, funded to the tune of $100 million over five years, also aims to increase Australian knowledge of and connections to Asia through study, work and internship programs.

Diplomacy is also critical; our partnerships in the region must be about more than commerce. Relationships need to be cultivated steadily and assiduously, including with those countries in Asia, and elsewhere, which are playing or are likely to play pivotal roles in regional and global politics. The recent push to increase Canada’s diplomatic presence in Asia, which had waned under both Liberal and Conservative governments, is welcome but does not go far enough. We have a lot of ground to catch up. As Singapore’s senior statesman, Kishore Mahubani, who was once a foreign student at Dalhousie University in Halifax and is now dean of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy in Singapore, noted in 2012: “Canada has neglected Asia. Canada has paid very little attention.”

Reversing this state of affairs will require a concerted and sustained effort. You will need to develop a comprehensive Asia-Pacific strategy to expand Canada’s market access and significantly increase our business, diplomatic and people-to-people contacts with the region. This should be a national campaign involving the provinces, major cities, exporting sectors, educational institutions, tourism and export development agencies, and other stakeholders—and it should be led by you, Prime Minister.

In developing this strategy, pay special attention to international education—Canadian students going abroad and international students coming to Canada—which builds long-term links between societies, expands the pool of Canadians who are prepared to operate in international environments and attracts talented young people to Canada. Governor-General David Johnston, who knows something about higher education from his years as a university leader, calls this the “diplomacy of knowledge.” His recent speeches on the subject are worth reading. They make a strong case for dramatically increasing the flow of exchange of students between Canada and other countries.

Canada’s current international education strategy, issued in 2014, sensibly aims to double the number of foreign students in Canada over the next decade. Beyond larger numbers, however, we should seek to attract the best and brightest to Canada by creating a major new international scholarship program that targets key countries, including in Asia. In its 2012 report, the federally appointed advisory panel on international education recommended that Ottawa fund 8,000 foreign-student scholarships over ten years. You should follow this advice. Among other things, it would be an investment in building Canada’s brand as a prime destination for international students.

The other side of this equation—sending Canadian students abroad—also deserves your attention. Only 3 percent of Canadian students participate in educational programs in other countries, a “miniscule” proportion, according to the Canadian Bureau for International Education, which also notes that more than 30 percent of German students go abroad. Among the Canadian students who participate in international programs, moreover, most go to the United States, Britain, Australia or France, and study in their first language. We are not preparing the next generation of Canadians to navigate a more complex world in which economic and political power is diffusing. The fact that only about 3,000 Canadian students were studying in China in 2012, for instance, ought to be a source of concern. Create a new scholarship program that will send 100,000 Canadian students on international learning experiences over the next ten years, including to the emerging countries of Asia.

Education, however, is just one element of an Asia-Pacific strategy. Business development is key. Take groups of young Canadian entrepreneurs on trade missions to China and to other emerging economies, and negotiate visa regimes to enable young international workers to be mobile and gain international experience over a two-year period. Sponsor “reverse trade missions” by inviting representatives from key emerging-country sectors to Canada, where they could attend trade fairs with Canadian businesses, as the Ontario Jobs and Prosperity Council recently suggested. Promote Canada as a hub for Asian multinational enterprises in the Americas. And establish an advisory council of eminent Asian political and business leaders to meet annually with you and senior government officials.

While the Asia-Pacific strategy is important, so is restoring positive and constructive relations with the United States, which will remain our principal economic partner for the foreseeable future. In 2013, more than 75 percent of Canada’s total merchandise exports went to the United States. Of these, more than half crossed the border by road or rail. Even in a digital age, therefore, ensuring that these land crossings remain open and efficient for travellers and goods remains a vital Canadian interest. But progress on improving the efficiency of the border has slowed. We need an engaged partner in the White House to drive this agenda forward and to overcome the entropy of the U.S. political system. However, convincing the American president to embrace this role will require—once again—skilful diplomacy.

Your first priority should be to improve the tenor of bilateral relations, but you also need to begin planning for the inauguration of a new president in January 2017—by developing a proposal for renewed continental cooperation. Here, too, there are many options to consider: Propose a new mobility agreement allowing more Canadians and Americans to work temporarily in the other country. Seek a Canadian exemption from U.S. “Buy America” laws and protectionist country-of-origin labelling requirements. Create a genuinely integrated cargo inspection system, so that goods entering Canada, the U.S. or Mexico need to be inspected only once, not every time they cross our shared borders. You could even explore options for eliminating differences in the tariffs that the U.S. and Canada charge on imports from third countries—also known as a customs union. As University of Ottawa economist Patrick Georges has shown, this would generate significant economic benefits for Canada.

Energy and the environment loom large in our bilateral relations, especially given Canada’s long-unanswered request for U.S. approval of the Keystone XL pipeline. Being an international laggard on climate change—arguably the biggest problem facing the world—has not helped our case. Canada’s environmental irresponsibility must end. Your foreign policy should include meaningful reductions in Canada’s carbon emissions and a more constructive approach to global negotiations of a post-Kyoto arrangement on climate change. To the greatest extent possible, you should do this in conjunction with the U.S., in order to avoid placing Canadian companies at a competitive disadvantage. Our two countries should resolve to make North America the most responsible producer of natural resources in the world. A continental cap-and-trade system, or coordinated carbon taxes, could be part of this arrangement.

Beyond climate change, you should revitalize Canada’s multilateral diplomacy on a range of global issues, including at the United Nations. We have all but abandoned our involvement in UN peace operations—even though the number of troops deployed in these missions is at an all-time high. These “next generation” missions tend to be more dangerous and complex than the traditional peacekeeping of the Cold War era, yet in many cases they are containing violence or helping to prevent renewed fighting after ceasefires have been struck. You should offer to provide the UN with the specialized capabilities—such as engineering companies, mobile medical facilities, in-theatre airlift, surveillance and reconnaissance capabilities, and civilian experts—which many of these missions need.

Some might see a return to UN peace operations as retrograde, but they would be wrong. Stabilizing fragile and conflict-affected states is an international security and development challenge of the first order. Most of the world’s refugee and humanitarian emergencies occur in fragile states. These countries are also home to half of all people who live below the $1.25-a-day poverty line. Moreover, chronic unrest and weak governance can create opportunities for transnational militants to establish a presence, to destabilize neighbouring states and to recruit internationally.

Canada should be at the forefront of a comprehensive international response to this problem. In some cases, this will involve assisting local and regional forces who are fighting groups that threaten civilian populations and international security, such as Islamic State. There is an important distinction, however, between helping these forces secure their own country and doing the ground fighting for them. In Iraq and Syria, the U.S.-led coalition has, to date, performed mainly a supporting role—training anti-Islamic State forces and conducting air strikes against Islamic State targets—but there will likely be growing pressure on Western governments to move their ground troops into front-line combat roles in the coming months and years. Beware mission creep. “Limited” military operations have an inborn propensity to become decidedly less limited over time.

Military action alone, however, is unlikely to create the conditions for stability in most fragile states. It deals only with the symptoms of instability, not its causes. NATO’s supreme commander, U.S. Air Force General Philip Breedlove, made this point last December in relation to Iraq and Syria. Long-term stabilization and de-radicalization strategies, he said, must focus on bringing jobs, education, health and safety to vulnerable people, as well as figuring out how to make governments responsive to their people. He is right. You should call for a more comprehensive international response to fragile states, one that addresses the causes of instability and radicalization, including poor governance and lack of economic opportunity, ideally before they threaten international security. Today, most fragile states are still far less violent than Syria and Iraq, but if we ignore them, or if we respond only to the symptoms of their unrest, all bets are off.

These proposals—on relations with Asia and the U.S., energy and the environment, and fragile states—are by no means an exhaustive list. As you choose your priorities, however, bear in mind that Canada needs to maintain a “full-spectrum” foreign policy that is global in scope. We are a G7 country and should behave like one. This also means investing in the instruments of our international policy: a superb diplomatic service, an effective and well-equipped military, and a robust development program.

In some areas of policy, it is our methods, rather than our goals, that require adjustment. Canada should, for example, continue to stand strongly with our allies against Russia’s aggressive behaviour in Eastern Europe, but we should maintain open channels of communication with Moscow, including on Arctic issues. We should uphold Israel’s right to exist and its security, but without diminishing the rights of Palestinians. We should continue Canada’s international campaign for maternal, newborn and child health, but without excluding reproductive rights, which are vital to women’s health. The World Health Organization estimates that unsafe abortions cause about 8 percent of maternal deaths globally, but Canada has nevertheless refused to fund safe abortions abroad.

The maternal and child health campaign is noteworthy for another reason: it underscores the importance of constructive diplomacy. Apart from the controversy over Canada’s position on reproductive rights, the overall campaign has “helped to significantly reduce maternal deaths” since it was launched in 2010, according to Maureen McTeer, a noted feminist and the Canadian representative of the international White Ribbon Alliance for Safe Motherhood. It has worked, in part, because Canada joined forces with a broad array of partners—like-minded countries, philanthropic foundations, civil society organizations and global institutions—in pursuit of a common set of goals.

This is a promising model, particularly given the changes now taking place in world affairs. The diffusion of power to rising states and non-state actors is making collective action even more difficult to achieve, as we see in the periodic paralysis of major multilateral organizations, from the World Trade Organization to the UN. Getting things done in a more crowded world—and finding solutions to complex international problems—will increasingly require mobilizing issue-specific “action coalitions” of state and non-state actors.

As it happens, Canada is well positioned to perform this role. We have done so in the past, assembling coalitions in the 1990s that produced a ban on anti-personnel landmines and established the International Criminal Court. In fact, Canada’s tradition of diplomatic entrepreneurialism dates back much further—and for good reason: working constructively with a broad range of partners to tackle international problems has often served both our interests and our values. When Canadian diplomats contributed to the construction of the post–World War Two international order, they did so not only to foster international peace, although this was certainly one of their goals. They also saw an opportunity to increase Canada’s influence—by making Canada a respected and valued partner. As Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent once said, we could be “useful to ourselves through being useful to others.”

When St. Laurent spoke those works in 1947, he was setting forth a Canadian foreign policy strategy for a then-new post-war world. Today, we are living through yet another period of global transformation. Your challenge, Prime Minister, is to chart a new course for Canada—one that will safeguard and enhance our prosperity, security and well-being for the years to come.

Some things, however, do not change. Whatever objectives you may set forth, St. Laurent’s maxim will remain true: In international affairs, Canada’s strength comes not from telling others what to do, but from working with others toward shared goals.

About the Author

Roland Paris is director of the Centre for International Policy Studies at the University of Ottawa. An academic and former federal public servant under both Liberal and Conservative governments, he has provided policy advice to international organizations, national governments and political leaders—including, most recently, Liberal leader Justin Trudeau.