Tweet

In the draft budget for 2015 tabled by the City of Ottawa, one seemingly small but critical program is at risk: Healthy Babies Healthy Children. Launched by the province of Ontario and run by the Ottawa Board of Health, it is program on the proverbial chopping block that is worthy of national attention.

The early years – from birth to age six – are critical in a child’s development. Healthy Babies Healthy Children helps to support pre-natal and post-natal care for all citizens in the city. Three avenues of programs and services provide this support.

First, to help parents learn about pregnancy, preterm labour, breastfeeding, and caring for an infant, free online and in person prental classes are offered in English and French in various locations across the City throughout the year. In addition, public health officials facilitate ‘pregnancy circles’ that are offered in English, French, and Chinese, for expectant parents who may need extra support.

Second, after a baby is born in Ottawa, a public health nurse calls to check in on the health of the newborn. Asking fundamental questions, these simple phone calls connect parents to the outside world at a time of vulnerability and uncertainty. It lets families know that they are not alone and that there is someone out there that they can call if need be.

Third, drop-in centres are open on a rotating basis every day of the week all across the city. Facilitated by public health nurses, nutritionists and lactation consultants, the centres provide a safe and warm environment for parents with young infants to visit. Here, babies are weighed, ‘tummy-times’ are had, and communities are built. Moms having problems with breastfeeding can learn new tricks to make it easier for them, parents worried about the development of their babies can have questions answered, nurses are given face-to-face opportunities to explain the benefits of vaccines (all the more important given the recent measles outbreak), and everyone gets to share their stories about the joys and challenges they are facing with young infants at home.

Individual benefits for babies from such programs are clear. While nothing really prepares you for bringing a baby home, prental classes nevertheless give parents good information to increase infant well-being. Regular weekly weigh-ins that is charted provides early warning signs if something is wrong. Or, weekly weigh-ins may calm nervous young parents keeping them out of doctors’ offices. Even as early as three months, contact with other babies furthers cognitive and emotional development. Such individual benefits for the babies should be enough to convince any government to keep these programs running.

Benefits, however, are not restricted to the individual babies. Collective benefits for families and the community writ large are invaluable.

Post-partum depression, for example, is a major illness that can affect moms, dads, and parents who adopt [1]. Caring for an infant is often extremely isolating, amplifying the symptoms of post-partum depression. Having a safe space to visit and regularly meet with other people can help parents see if they are experiencing the symptoms of post-partum depression and seek the help that they need.

Ottawa, like many cities across Canada, is also filled with families that have just moved who don’t have access to an extended network of aunts, uncles, and grandparents that they can rely on. The drop-in centres held under the Healthy Babies Healthy Children program help build communities. From clothing exchanges to informal parental baby-sitting networks, these centres provide a hub for new residents helping them to integrate into the place that they are now calling home.

That, in a nutshell, is the Healthy Babies Healthy Children program and some of the key benefits that it offers. What, then, is the problem?

In her report submitted to the City, Medical Officer of Health, Dr. Isra Levy draws attention to the fact that Ottawa Public Health faces ‘significant long-term funding shortfalls’ caused by inflation and insufficient support from the Government of Ontario due to caps on provincially funded programs [2]. A funding gap has thus appeared.

To fill the gap, Ottawa Public Health is planning to restrict access to the three avenues of service for clients with ‘identified risk factors’. In other words, a program that was once open and available for all families in the city will now be limited to only those who meet defined criteria.

If the City does this, a universal program will be transformed into what policy wonks call a means-tested service. A poor strategy for two reasons.

First, restricting the program to ‘at-risk’ clients will increase the administrative costs of the programs. Staff members will now need to spend time determining whether or not a person should actually access the service, rather than simply working with everyone who comes through the proverbial door.

Second, universal programs help build solidarity and foster shared understanding. Such programs also have a greater number of people concerned that are ready and willing to fight for them should they be threatened with cuts or cancellation. When services are means tested, such advocates disappear and, overtime, the benefits are at a bigger risk of withering or vanishing altogether.

Contrast this proposal with a long-standing practice in Finland. There, for more than 75 years, expectant mothers are given a box by the state. With clothes, sheets and toys it gives all Finnish children, regardless of their background, the same start in life. And, according to researchers like Mika Gissler, professor at the National Institute for Health and Welfare in Helsinki, the boxes have played a major role in improving family health overall in the country [3].

So what should happen? To start, the Province of Ontario should index the funds to ensure the costs of the programs it launched are sufficiently covered. Ironically, Ontario is subjecting municipalities across the province to the same critique often lobbed at the federal government: the province started a ‘boutique program’ while leaving the other level of government holding the financial bag. The City of Ottawa could be a bellwether for other municipalities across the province, and the entire initiative may be on route to its demise.

Even more importantly, particularly given Canada’s egregious and stubborn rates of child poverty, provinces and territories from coast to coast should offer similar programs and improve on the Ontario model [4]. An integrated yet diversified network of such programs dedicated to young children should be established and made available and accessible for all families regardless of where they live in the country. Healthy babies and healthy children should be a benefit enjoyed by all who live in Canada.

Tweet

Jennifer Wallner is an Assistant Professor at the University of Ottawa’s School of Political Studies. She can be contacted at jennifer.wallner[at]uottawa.ca

Tag: Economy

Blog: One-size childcare policy fits no-one

Tweet

There are a little more than 4 million children in Canada aged 0 to 12 years.[1] They need care and education. I don’t think anyone really disputes this–youth 13 and older obviously also have needs for care and education but they’re not the focus of this post. In most cases, decisions about that care and education are made by parents or legal guardians who will have the bests interests of their children at heart. I don’t think anyone disputes this either. Those children and the families making decisions for them are really, really diverse. So why do we keep trying to produce national public policies on child-care that are one-size solutions?

Sometimes one-size fits all means everyone gets the same kind of choices for childcare.

Supply-side solutions look for ways to increase the number of spaces for children in quality childcare programs. For example, Quebec’s provincial childcare system provides all families with a regulated space in a childcare centre or in licensed homecare and regulates the out-of-pocket costs to parents. In a long-overdue move the province has started to tie that fee to household income. The 2005 federal-provincial agreement on childcare was similarly intended to increase the supply of regulated spaces in the rest of the country. All provinces in the country provide some financial support (from some combination of federal transfers and their own tax revenues) for the early learning and care services in their jurisdiction. In 2006-07, there was also a short-lived federal effort to look for recommendations to encourage employers to create more childcare spaces for their employees. That last effort ended quietly.

It’s not totally clear we have a supply-side problem when it comes to learning and care for kids. Our indicators on the supply of childcare in Canada are a bit problematic in that they exclude other options used by families like after-school recreational programs and homecare with too few clients to require a license.[2] What we do know is that there were 585,274 licensed spaces (in centres or licensed homecare) across Canada (outside Quebec), which makes it sound like as many as 85% of kids are going without childcare from infancy to middle school. In reality, we have to adjust that ratio to account for other factors like access to parental leave, private care arrangements and programs that may be high quality and developmental but fall outside provincial regulation. Furthermore, depending on the age of the child, between 40 and 60%[3] of families say they don’t use any daycare services (note the switch here to “daycare”) at all. How do they manage? Well, probably through some combination of private arrangements, adjusting their work hours and relying on things like full-day kindergarten (where they can) and after-school recreational programs. When parents are asked what matters most to them when they choose their childcare, parents report that location, trust in the provider and affordability are, in descending order, their 3 primary criteria with location by far the most frequently-cited factor.[4] So, getting the supply-side right has to mean attention to a really wide range of types of care, the market price of that care and even the minutiae of where that care is physically located. That’s a tall order if you want to rely on just one policy instrument, no matter what that one instrument is.

Sometimes, one-size fits all means giving everyone the same financial support, regardless of need or ability to pay. This is when really strange things can happen.

Demand-side solutions look for ways to reduce the need for childcare or to subsidize the market price of that care. For example, all provinces outside of Quebec offer income-tested subsidies for licensed childcare services. Quebec did away with subsidies when it introduced its universal daycare plan which has led to an interesting puzzle: Among households who say they use childcare, Quebec households are more likely to say they pay $10 a day or less, but modest income households (making under $40,000/year) are significantly more likely to say they pay $0 out-of-pocket for that care if they live outside Quebec than inside Quebec.[5] In short, swapping subsidies for flat fees seems to mean that costs for childcare are lower on average across all households but are actually higher for lower income households.

Federally, there are two key instruments intended to help families with the costs of childcare. The Child Care Expenses Deduction (CCED) lets parents deduct eligible out of pocket childcare costs, within certain limits. It was recently increased to $8,000 for each child under age 7 starting in the 2015 tax year. When the 2005 federal-provincial supply-side agreement on childcare was cancelled, the money was used to create a new flat cash transfer of $100 per month for each child under 6 years–the Universal Child Care Benefit (UCCB). Financing the UCCB also meant diverting money out of the income-tested Canada Child Tax Benefit system.[6] The UCCB was recently expanded so each child under 6 creates a flat entitlement to $160 per month and each child aged 6 to 18 years generates flat entitlement to $60.

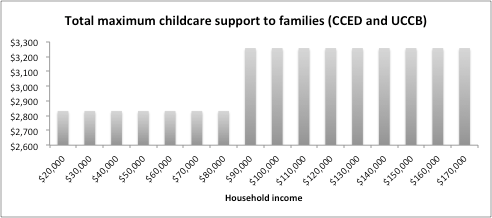

The CCED and the UCCB are both responsive to parental income in some weird ways. The CCED has to be claimed by a working (or student) parent with the lower income and the UCCB is taxable in the hands of the lower income parent (regardless of their labour force activity). Let’s take a simple case, where two parents in a household have equal incomes, or at least incomes in the same federal tax bracket. Figure 1 (below) shows the maximum federal benefit they could receive out of the CCED and UCCB for one child under 7 years of age in the 2015 tax year.

The net effect is that direct federal demand-side support generally rises with household income. The UCCB purposefully pays the same amount, before taxes, no matter a household’s actual expenditure on learning and care. The CCED lets families claim some tax relief only after they’ve spent the money on eligible forms of daycare–an approach that works far better if a family can afford the cashflow pressures in the interim and has enough tax liability get some real benefit out of a deduction.

Policy proposals that promise the same amount of money to all families, whether they are supply-side or demand-side solutions, are politically attractive. They make for nice pithy bumper-sticker commitments that are easy to communicate. But they come with real problems because neither is able to adjust to the needs and means of Canada’s diverse families. In either case, some strange things seem to happen.

Maybe the primary problem in the current childcare policy debate is that it has pitted families who use daycare against families who don’t. Families who use daycare are reduced to supporting a one-sized supply-side approach. Families who don’t are reduced to supporting equally one-sized demand-side option instead. In neither case does the debate acknowledge or respond to a more realistic range of preferences, needs and ability to pay.

What if instead, our starting point was that:

- Childcare is what all families provide for their kids.

- All of those kids need learning and care.

- Many, but not all families meet their kids’ needs for learning and care through daycare.

- Different families will have different demands for early learning and care in their community.

- Different families will have different abilities to pay and out of pocket costs.

There are lots of different levers that could be used on the family policy front and it’s time they started to be used in more nuanced, integrated ways. This route doesn’t lead to simple policy solutions of $X per day or $X per month. Maybe we’ll just have to start making some bigger bumper-stickers.

Tweet

Jennifer Robson is an Assistant Professor at Carleton’s School of Political Management. Contact her at jennifer.robson[at]carleton.ca

From the End of History to the End of Progress

Tweet

A few years ago, we began noticing something very different about the way the public looked at the economy[1]. The public seemed to believe that we were encountering an end of progress. The idea of a “better life” or what is known to the south as the American Dream seemed to be slipping away. Among citizens of both Canada and the United States, there was a growing recognition that the middle class bargain of shared prosperity, which had propelled upper North America to pinnacle status in the world economy in the last half of the twentieth century, was unravelling.

In this brief consideration of the political implications of the problems of the middle class, we will examine both perceptions and behaviour (and values). Our work reflects the grand insights of major recent scholarly work by Daron Acemoğlu, Thomas Piketty, Richard Wilkinson, Miles Corak, and others. We believe that this percolating crisis of the middle class is the greatest challenge of our time and we have argued this narrative to very senior audiences in Canada and the United States – whoever will listen and act.

Despite near public consensus on the severity of the issue, and impressive empirical and expert support, many in the media and elsewhere deny the problem. And yes, there is still relative prosperity in the Canadian economy – we certainly aren’t Spain, let alone Greece. The trajectory, however, is clearly to stagnation and decline, except for those at the top of the system.[2]

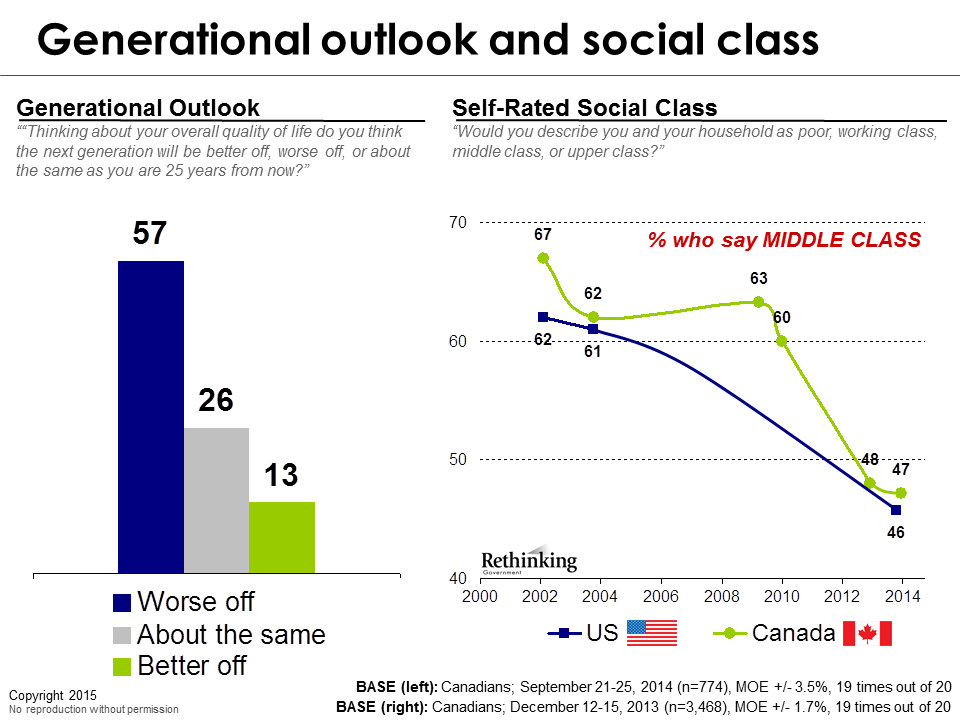

The public are not deluded, nor hysterical. The clarity of public concerns around the issue of middle class decline is remarkable. Moreover, when we unpack this across generational cohorts we can see that the unravelling is much more evident as we move from seniors to young Canada. So while still eminently fixable, the trend lines lead to a very gloomy prognosis which is currently infecting public outlook and threatening to become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Fears are highest when turned to the future, particularly concerns about retirement, and the fate of future generations. Whereas the middle class used to mean one could attain a house and a few luxuries and a better life than one’s parents it is now all about security, which has become the elusive lacuna as it applies to the ability to get by and to retire with security. The grey outlook on the present turns almost black as the public ponder the fate of future generations.

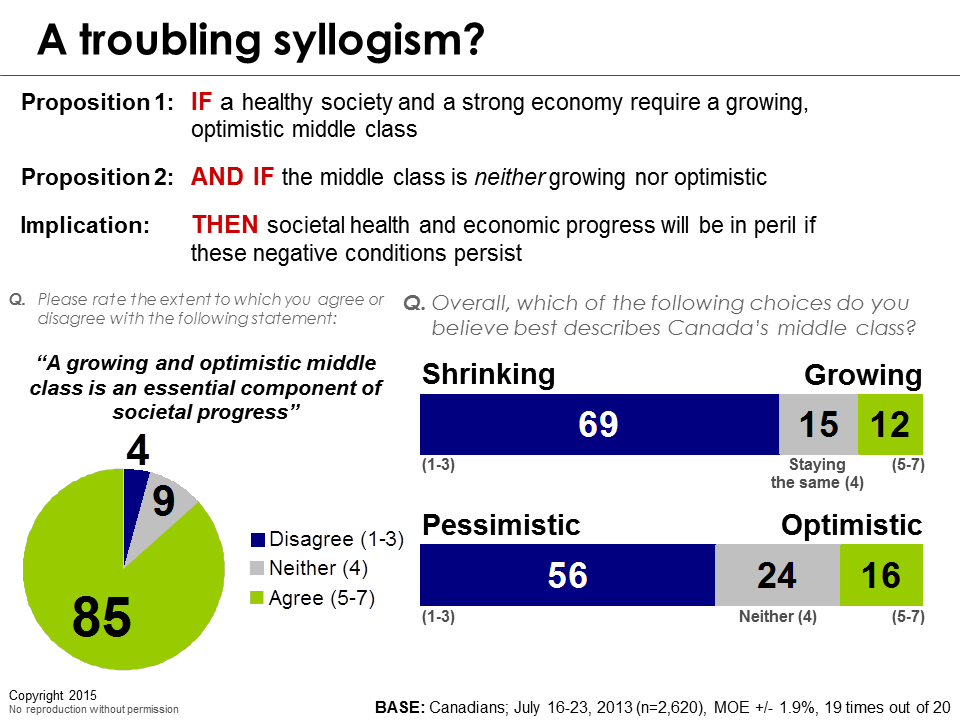

Consider the troubling syllogism laid out below:

There is a virtual consensus that a growing and optimistic middle class is a precondition for societal health and economic prosperity. This consensus position reflects the historical record of when nations succeed.[3] Yet if this consensus is correct, we note with alarm that almost nobody thinks that these conditions are in place in Canada. To the contrary, the consensus view is that the middle class is shrinking and pessimistic.

What has changed?

There are important barometers of confidence and we have tested these the same way in repeated measures for twenty years or so; the trajectories are clear and revealing. Never in our tracking has Canada had such a gloomy outlook on the economic future. Never in our tracking has the sense of progress from the past been so meager. The right wing commentariat may seize upon partial stories/research to suggest: i) this is a non-issue – only of concern to “wonks”; and ii) things are swimmingly well and even if public show fears, they are being foolish. We say the public are right.

The point isn’t that Canada is in a state of privation and economic distress – it clearly isn’t. The point is that the factors that produced progress and success don’t seem to be working in the same way anymore. And the problem is accelerating as we move down the generational ladder.

The current generation sees itself falling backward and sees an even steeper decline in future. The typical optimism of youth is very muted as they encounter an economy that doesn’t seem to offer the same promise of shared progress available to their parents and grandparents.

So it appears that we have at least temporarily reached the end of the progress, the defining achievement of liberal democracy.

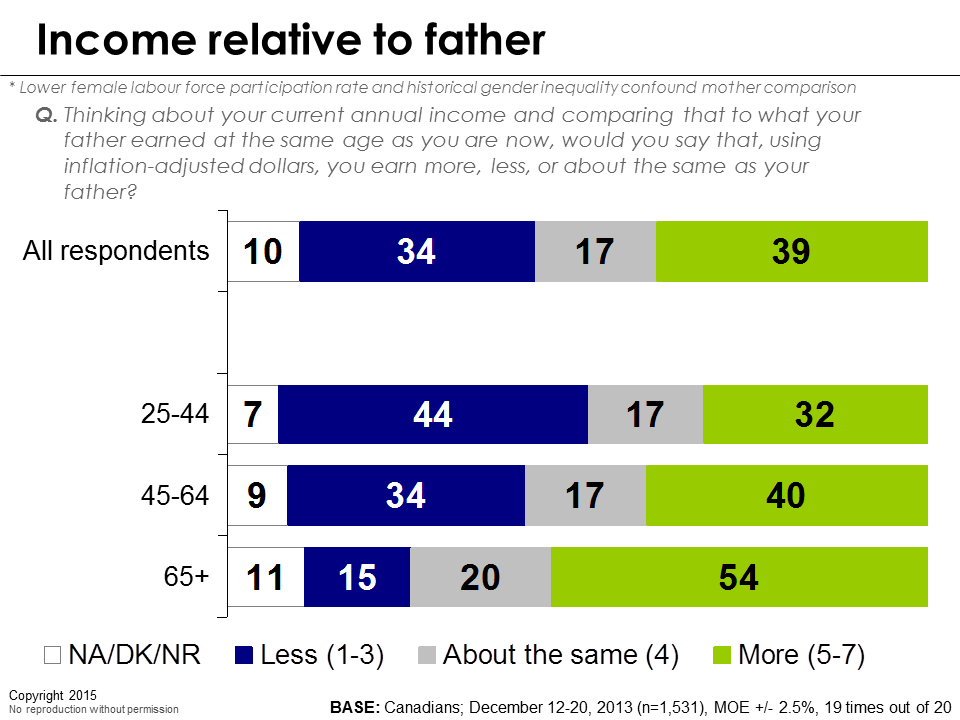

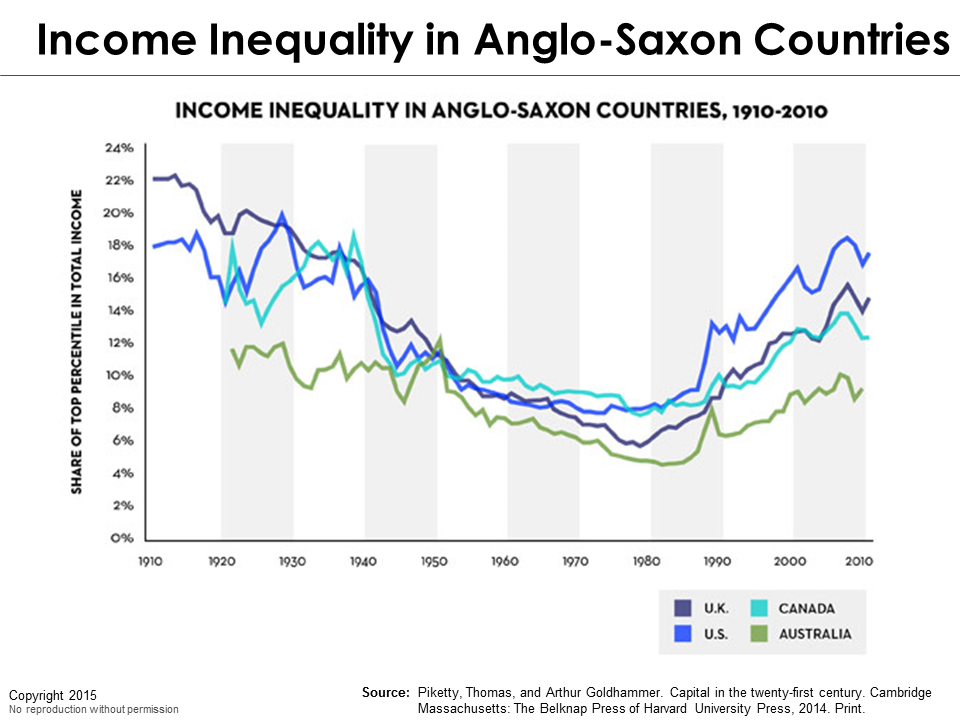

Vertical mobility eroding

The chart above shows a sharp rise in the rate of downward intergenerational mobility as we move from seniors to younger Canada (a nearly threefold increase). Arguably, the prime driver of this is rising inequality which is increasing quickly across all advanced western economies.[4] Notably, as Miles Corak notes,[5] the incidence of upward vertical mobility across generations is dropping most sharply in those places which are becoming more unequal at an even faster pace.

The economic ladder is missing rungs in the middle and people are less motivated to try climbing with those conditions in place. Merit is less relevant as the system is now “stickier” at the top and bottom of the social ladder. This failure of the incentive system is hobbling innovation and effort and creating a more tepid growth pattern where the relatively more slowly growing pie is appropriated by an ever slenderer cohort at the top.[6] We are literally killing the goose that lays the golden eggs underpinning healthy middle class economies.

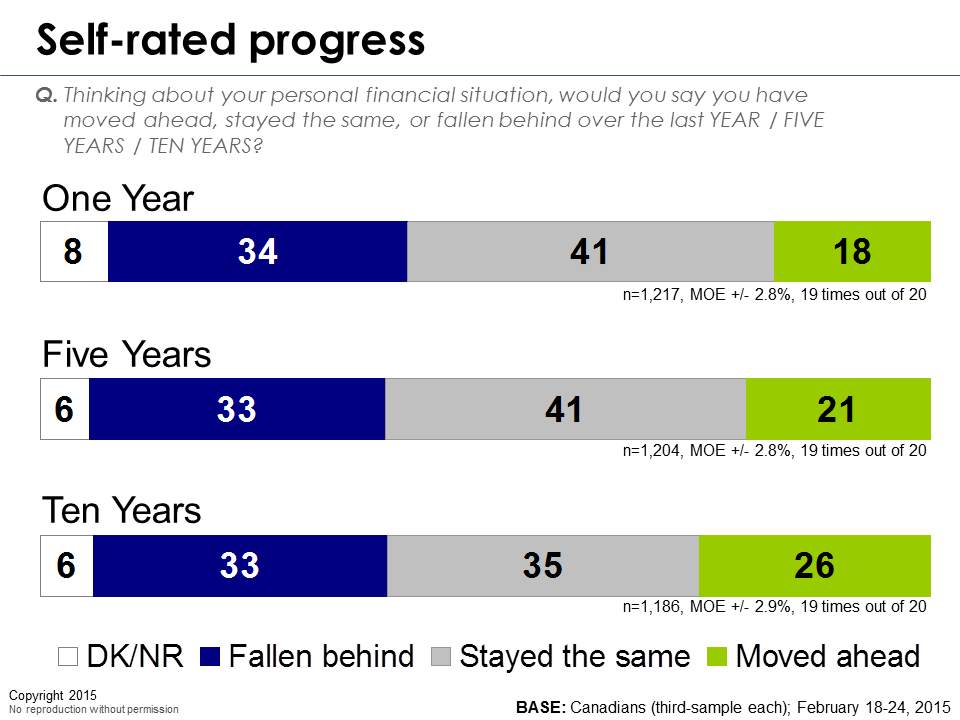

If one thinks this problem is self-correcting or going away, ponder the chart below which is a couple of days old. Very few Canadians think their financial situation is improving but the sense of progress seems to get smaller as we move from ten to five to one year comparisons. What does it say about an economy which defines shared progress as an economic and moral imperative that less than one in five thinks their lot improved last year?

For those who think it has always been like this or that Canada is either immune or charting a differing path, it is not so. In broad brush strokes, four Anglo-Saxon economies have followed the same curve, which seems to be leading to a reproduction of the original gilded age of robber barons which predated the great depression.

Conclusions and going forward

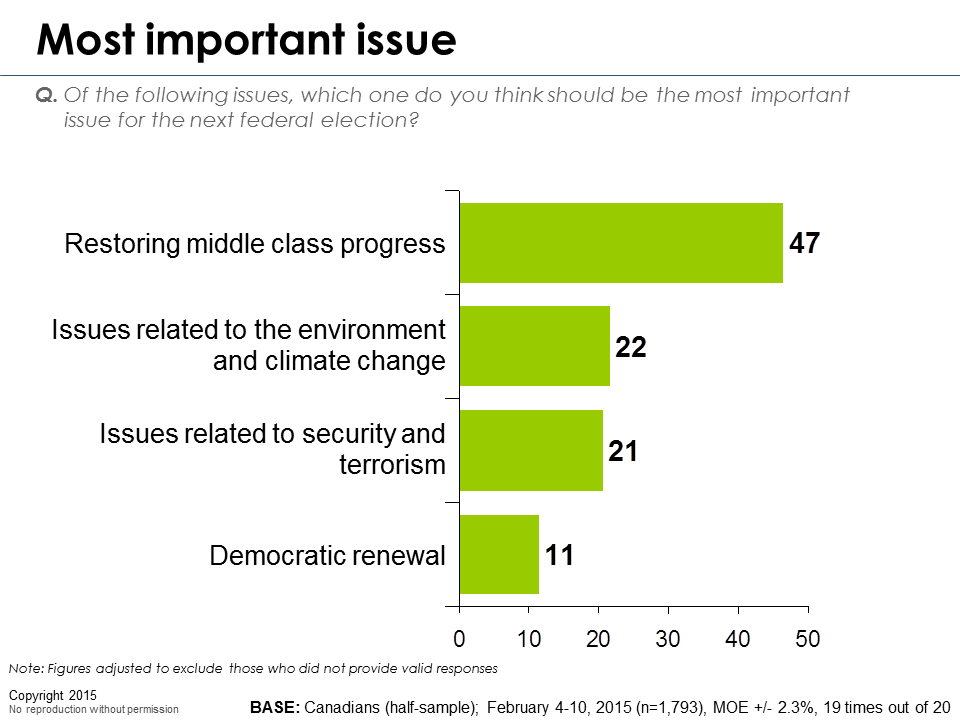

Will the issue of middle class progress be an issue in the coming election? There are good arguments that once the emotion and chauvinism surrounding terror and ‘cultural’ issues fade, this issue will reassume its pinnacle position.[7] What will Canadians think in the fall when the inevitable early enthusiasm for another Middle East adventure doomed to yield disappointment yet again fades? They will look at a relatively moribund Canadian economy lurching along at sub-two-point growth with nothing available for any members of the depleted middle class. They will ponder the prudence of a long term bet on the short term prospect for carbon super power status. They will look enviously at an American economy moving at twice the clip of ours under the explicit framing of what Obama calls ‘middle class economics”. They will look to their prospective leaders and ask who has the most plausible blueprint to restart middle class progress?

Tweet

Frank Graves is founder and President of EKOS Research, and is one of the country’s leading applied social researchers, directing some of the largest and most challenging social research assignments conducted in Canada.

Unemployed and Underemployed Youth

In this new background paper from Canada 2020, we take a look at the employment landscape facing Canadian youth.

The paper’s premise is built upon a simple and well-known fact: Canada’s future economic success will depend on the strength and quality of its human capital – and therefore its investment in young people.

What this paper is not built on, however, is this: that some “special’ status that should be afforded to young people on the premise of intergenerational goodwill.

Rather this report suggests that there are immediate and future economic costs tied to the unemployment and underutilization of young workers.

To gain a better perspective on whether Canada is leveraging its human capital investment efficiently and striving for efficient labour market conditions, especially when it comes to its young people, this report sheds light on recent developments on youth unemployment and underemployment trends.The report also looks at the potential that entrepreneurship holds for young people in today’s workforce, and

the type of support required to attract youth to the sector.

Download PDF

An austerity agenda hidden in an ‘NDP budget’

The Ontario government tries to satisfy everyone.

How does a minority government mired in a big deficit and in the grips of weak economic growth craft a budget that satisfies the NDP opposition and keeps the financial markets content?

Bob Rae, premier of Ontario for five years in the early 1990s, faced economic and fiscal challenges like this throughout his time in office but failed to triangulate such disparate interests. Paul Martin — undisputed master of the fiscal and economic universe for nine years as finance minister under Jean Chrétien — headed a minority government that negotiated a budget in 2005 with the NDP that managed to secure the support of Jack Layton, but was frowned upon by Bay Street.

By contrast, the inaugural budget of Premier Kathleen Wynne and novice Finance Minister Charles Sousa has likely succeeded where these and previous attempts at placating left and right have failed. The NDP will undoubtedly support the budget because it meets most of their demands. And Bay Street should be quite satisfied with a fiscal plan that is consistent with their agenda.

Most of the commentary has characterized this budget as a major victory for the NDP, upon whose support the Wynne government relies to survive, Tim Hudak’s Conservatives having committed to vote against it regardless of its contents. It has even been suggested this is more NDP Leader Andrea Horwath’s budget than anyone else’s.

To be sure, Horwath’s main demands were met, notably closing some corporate tax loopholes, putting in place a youth unemployment strategy, establishing new supports for small business, additional funds for northern Ontario infrastructure and committing to a legislated 15-per-cent cut to auto insurance premiums.

That said, the most important element of the budget runs rather contrary to NDP orthodoxy. This part is buried toward the end of the lengthy tome under the heading “Ontario’s Recovery Plan.” It is in here that we find the stuff the financial markets will like. And it is here that we locate the method to execute a comment Sousa made in a speech on April 22: “The most important and fundamental thing that we can do, together, to secure our future prosperity is eliminate the deficit.”

Put simply, the austerity drive — eliminating Ontario’s $10-billion deficit by 2017-’18 — is the cornerstone of the Wynne government’s agenda, even if the government hasn’t emphasized this.

Importantly, this deficit elimination objective will be achieved by holding program spending increases to less than one per cent per year on average over the next five years. Which might not sound terribly ambitious unless you consider that this is under the rate of inflation, meaning it equals a significant real cut in government spending.

Consider further that health care spending — which has been rising seven per cent per year on average for 30 years — eats up 42 per cent of Ontario’s program costs.

Then add to that the fact that we are on the cusp of the “grey society” — a period of unprecedented aging demographics which will put huge upward pressure on health care budgets — and one starts to realize the magnitude of the fiscal challenge Wynne and Sousa have set out for themselves. The budget document acknowledges this, stating that holding program spending rises to less than one per cent for years to come “will require some difficult choices.” Indeed it will.

Most of these choices have not been grappled with in Budget 2013, and lie in the future for the Wynne government. And despite dire warnings of its imminent demise, this government will almost certainly have a future of at least a few more months, if not another year and another budget.

The Wynne government’s effort at fiscal and economic planning has demonstrated skill on the part of the budget’s architects. They have crafted a document that both left and right can find their values reflected in, which is no small feat. That, in a sense, seems to be the essence of Liberalism today. By injecting into the budget some NDP inspired initiatives — and then emphasizing these publicly — the government is almost certain to survive. And by committing to a fairly tough austerity agenda — even in the context of weak economic growth and relatively high unemployment in Ontario, which might argue for rather less austerity — the government maintains its fiscal prudence credentials. The budget is an impressive piece of political strategy.

In the final analysis, however, what we really have here is a scene setter for a second Wynne-Sousa kick at the fiscal and economic can in a year.

Budget 2014 is where the rubber really hits the road — where the premier and finance minister will have to make some fundamental choices about the basic direction of and role for the Ontario government in the economy and in the lives of citizens.

Margaret Thatcher, Kathleen Wynne, Alison Redford and the politics of conviction

This week saw the passing of former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, one of the most influential politicians of the 20th century and probably the greatest female political leader of modern times. It is a truism that Thatcher led a revolution in the U.K. and beyond, one of the hallmarks of which was the notion that cutting taxes should be a central goal of modern government. Thatcherism, as it came to be called, in conjunction with Reaganism, its brother doctrine in the U.S., held that tax cuts were the cure to most of the economic and social ills that afflicted western democracies in the 1970s and 1980s.

The tax-cutting ideology espoused by Thatcher and Ronald Reagan reverberated far and wide, transforming the political right in some countries, but also having an impact on more moderate, centrist governments. The Chrétien Liberals, we should recall, boasted 13 years ago about bringing in the largest tax cut in Canadian history. This set a trajectory for federal tax reductions of various kinds that continued under both prime ministers Martin and Harper, the latter of whom took this ethos to absurd extremes when he suggested all taxes are bad.

At the federal level in Canada, for 15 years and spanning three different governments, the only acceptable direction for taxes has been down. Any politician who hints at the notion of a federal tax increase faced pillory if not political destruction. The ideological groundwork laid by Thatcher in the 1980s had a big influence on this world view taking root in Canada.

The worm, however, seems to be turning in this country on tax policy, at least at the provincial government level. And it is turning due to the ascent of two new women politicians on the Canadian scene — Premier Alison Redford of Alberta and Kathleen Wynne of Ontario. Together, these premiers may be on the cusp of sparking a minirevolution of their own on the issue of taxes. Both are courageously suggesting that perhaps some taxes will have to be increased. In so doing they are challenging a received wisdom that has gripped this country for two decades.

Wynne is basing her government’s entire agenda on the idea that Ontarians are going to have to pay more in taxes or other charges in order to generate the revenue needed to fix the chronic public transit issues that have afflicted the province — especially the Greater Toronto-Hamilton Area — for a generation and that undermine both quality of life and economic productivity. It is a breathtakingly sensible idea that runs headlong into the anti-tax red meat Ontarians have been fed for many years, stuffed down their throats today by both Conservative Leader Tim Hudak and Toronto Mayor Rob Ford.

For her part, Redford’s government has committed heresy in Alberta by suggesting that her province’s minimalist carbon tax might have to be more than doubled to have the desired effect on oilsands emission reductions. That Redford has even raised this issue in a province with the most anti-tax political culture in Canada, that prospers or slumps on the fortunes of the oil industry, borders on the heroic.

The nascent tax reform agendas emerging under the Wynne and Redford governments are potentially revolutionary in their longer-term implications if they succeed in sparking a conversation among Canadians about the appropriate role, levels and uses of taxes, and in the process recast two decades of anti-tax political discourse. Wynne and Redford might in fact be putting the first nail in the coffin of the conventional view that any talk of tax increases is political suicide in this country.

Margaret Thatcher famously described herself as a conviction politician, one who would not be dictated to by public or elite opinion. While Kathleen Wynne and Alison Redford — Liberal and Progressive Conservative respectively — reject Thatcherite policy ideology, they too appear to be conviction politicians in their own right. Both women seem to genuinely believe that the specific tax increases they are suggesting are good public policy choices that are needed to improve the quality of life, economic prosperity and environmental sustainability of their provinces, even if they might prove to be less than popular among citizens.

It is worth remembering that the last major act of Thatcher’s government was the introduction of the “community charge,” known euphemistically as the “poll tax,” one of the most controversial policies of her time in office. As premiers Wynne and Redford embark upon their own tax reform agendas they can take some comfort from the fact that even Maggie Thatcher — the inventor of conviction politics and one of the leading proponents of tax cuts during her era — believed in some tax increases.

#Budget2013 – Market intervention, conservative style

The reviews of Budget 2013 are in. It is a big yawn. A nothing Budget, a one- day wonder in terms of press interest, most of the new measures in it having been leaked beforehand.

This misses a core point. Budget 2013 is remarkable for one thing—the Conservative government has embraced a degree of market intervention we have not seen before.

Conservative commentators like Andrew Coyne, the Canadian Taxpayers Federation, the Fraser Institute and the National Citizens Coalition have lamented for years that the Harper government has strayed from conservative principles because it has been big spending and state expanding. The Harper government’s fiscal record, say these critics, is anathema to conservative principles and history. The critics are of course wrong. Big spending has been the hallmark of every national level conservative government in North America for going on thirty five years. Ronald Regan, George Bush 1 and 2 and Brian Mulroney delivered to their electorate massive deficits, ballooning national debts, and major expansions in the size of the state. If you believe the critics that the Harper government has been big spending and has expanded the size of the state you can be secure in the knowledge that this sits squarely within mainstream North American conservative governance history.

What is new for conservative governments in this country, however, and what runs afoul of three centuries of conservative orthodoxy—all the way back to Adam Smith–is micro economic market intervention, what is sometimes pejoratively referred to as “picking winners” or “industrial policy”. Too its credit, the Harper government’s 2013 Budget shows a willingness to depart from the conservative orthodoxy that the free, unfettered market always delivers the superior economic outcome. Fortunately, this orientation sits squarely in the wheel house of most governments, regardless of political stripe, in most advanced industrial countries.

The 2013 Budget, then, gives us a glimpse of a government that is acting much less like a tribe that subscribes to the theology of Milton Friedman and Frederick Hayek, and much more like a government that wants to experiment with ideas that actually work. In this connection, Budget 2013 contains three welcome market interventionist initiatives of note.

The first relates to the well-known problems of the Canadian labour market, specifically the skills mismatch that exists across the country, in which many employers cannot find workers with the requisite skills to fill jobs. Five years ago, the Conservatives introduced Labour Market Agreements (LMAs), whereby Ottawa transferred, with no strings attached, $500 million per year to the provinces to improve labour market outcomes in their jurisdictions. Half a decade of this hands- -off approach has evidently left the feds underwhelmed, as the skills mismatch has intensified. As a result, going forward, Ottawa will play a more active role in labour markets through the creation of a new Canada Jobs Grant—funded out of the LMA envelope—a $5,000 grant to individuals to be matched by employers and provinces to help ensure workers get the training they need to fill the jobs the labour market is offering. The free market and the provinces will no longer be left to their own devices in resolving Canada’s skills mismatch. Ottawa is coming to the rescue.

The second welcome market intervention contained in the 2013 Budget is the response to the panel headed by David Emerson, former Minister of Industry and Trade, mandated to review Canada’s aerospace policies and programs.

It is a truism that the global aerospace industry is dominated by government interventions of various types. Governments the world over have concluded that aerospace is an industry worth having and worth spending taxpayers money on because of the relatively unique positive spillovers that accrue to the economy as a whole from this sector. Subsidizing aerospace is even supported by a body of serious economic theory—so-called strategic trade theory—that Nobel prize winning economist Paul Krugman pioneered thirty odd years ago.

To its credit, the Harper government seems to have been persuaded that a new, yet modest, market intervention in the Canadian aerospace sector is warranted. Hence, Budget 2013 has committed to establish an Aerospace Technology Demonstration Program, with funding of $110 million over four years. This program will help Canadian aerospace firms bridge the financing gap for large scale technology demonstration projects, which if left un-bridged can cost business opportunities. This is a relatively low-cost and welcome market intervention that could make a big difference for the competitiveness of Canadian aerospace firms in the global marketplace.

Finally, after decades of neglect from both Conservative and Liberal governments alike, Budget 2013 is embracing the notion that Canada needs some kind of defence sector industrial policy. This follows on the heels of the recent report led by Tom Jenkins, CEO of Opentext, which basically called for Ottawa to put in place, on an urgent basis, a number of measures that cumulatively amount to a Canadian defence industrial strategy.

Market intervention in the defence sector is of course also contrary to free market orthodoxy. Yet governments the world over have recognized at least since the Second World War that this industry operates in a managed market, where governments are the main, and sometimes only, customers. And for a variety of complex national security, economic and sovereignty related reasons, most governments around the world have chosen to put in place various types of market interventions to support domestic defence suppliers. Canada has been a weird and almost inexplicable outlier in this respect. Budget 2013 fixes our outlier status with its commitment to implement the Jenkins panel report and establish a Canadian defence industrial policy.

This, then, is why Budget 2013 matters. Like all budgets, you can criticize it on many levels. But the idea that it is a pretty meaningless document misses a core feature of it. Budget 2013 signals an important shift—a maturing if you will– in the Harper’s government’s approach to economic policy, from one largely bound by free market orthodoxy to one that is more interested in policies that work in practice, but maybe less so in theory.

The New Clintonomics

Two weeks ago, two policy think tanks based in the U.S. and the UK — the Center for American Progress, founded by Bill Clinton’s former Chief of Staff John Podesta, and Policy Network, founded by former Labor Cabinet Minister Peter Mandelson and a group of former advisors to the government of Tony Blair — hosted a meeting of Europeans and North Americans in London. Canada 2020 was invited to attend this summit as the only non-European, non-American participant.

The meeting was framed as a trans-Atlantic dialogue on some of the major issues facing progressives today, in particular how to tackle the fiscal crises in Europe and the United States in the context of weak economic growth, and in a manner that doesn’t betray core progressive principles and values. The conference was also designed to bring together a new generation of progressive thinkers and politicians from Europe and North America, to regenerate the trans-Atlantic Third Way dialogue of the late 1990s that Tony Blair and Bill Clinton led.

Fittingly, then, the keynote speaker was President Clinton. In a forty-minute address, Mr. Clinton provided a road map for how America should deal with the fiscal and economic issues it faces. His prescription could be seen as amounting to a macro economic policy doctrine for the U.S. — a new Clintonomics if you will.

The foundation for the new Clintonomics rests on the notion that governments need to pursue what some might regard as two contradictory courses of action at once, what the President called “walk and chew gum’ economics. For Mr. Clinton, it is imperative that Washington invest significantly now, when US government borrowing rates are historically low, in the many things America needs to make it a more productive and competitive economy, notably infrastructure and education, but also in new industrial policy initiatives aimed at developing innovative sectors of the future. This investment will also provide needed short-run stimulus to an economy that is still operating well below potential over three years after the recession.

This bold investment agenda must, however, be anchored by a serious, credible, fiscal consolidation effort that will be planned, and expected, to kick in once economic growth takes firm hold. This, in Mr. Clinton’s view, is necessary in part to anchor expectations to help prevent the inevitable interest rate increases from rising too far and too fast and crowding out needed private sector investment.

While this was a serious policy talk from the President, he remains ever the pragmatic, centrist politician, not for a minute under-estimating the difficulty selling his economic remedy to the American public. Mr. Clinton observed that most Americans are fiscal conservatives, even if they are Democrats. Regardless of the economic merits of deficit spending in some situations, many Americans see piling on debt as immoral. As a result, those that argue for austerity now — the American right and the business community — will, in Mr. Clinton’s view, have an easier political sell to the American electorate than those that push for some variation of his agenda.

Nevertheless, the President made a compelling case that the complexity and variety of America’s core problems today — a grave fiscal situation, growing productivity and competitiveness issues, serious income inequality, and weak, post-recession growth — call for an equally complex range of actions, which might even appear contradictory to many people.

In the domain of American political economy, it seems walking and chewing gum is a lot harder than it sounds.

Omnibus budget legislation hits a new low

‘What does this have to do with the ways and means of the government?”

It was a question asked in the mid 1990s by government House leader Herb Gray in the early days of the Chrétien government, during a briefing he was having with finance department officials on the Budget Implementation Act (BIA). Gray, then a 35-year veteran of the Commons, had spotted a provision in the legislation that was non-budgetary, that had nothing to do with “the ways and means of the government.” To parliamentary purists like Gray, that is what budget bills were supposed to be restricted to.

The finance officials were caught flat-footed and had no answer to the veteran minister’s question. Nevertheless, despite Gray’s protestations, the bill remained as was and was introduced into the House of Commons.

Thus began a new era in Canadian politics — the era of the abuse of budgets and their implementing legislation. A period characterized by the increasing dominance of the finance minister and his department. An era in which the role of parliamentary committees in scrutinizing and amending legislation was disappearing before our eyes.

After 10 years in office, the Chrétien government’s budgets had grown from a slim 63 pages in length in 1994 to a bloated 380 pages in 2003. Not to be outdone, the final budget of Paul Martin’s minority Liberal government in 2005 was 450 pages long.

Budgets had morphed into governing agendas for the year rather than fiscal and economic statements that were restricted largely to taxation measures and the ways and means of the government. If a policy or program wasn’t in the budget, it either wasn’t happening that year or it was too trivial to worry about.

But the real abuse hasn’t been so much with the budget per se, but rather its implementing legislation. The 1994 Budget Implementation Act, or BIA, was 10 pages long. By the early 2000s, the BIA, then known euphemistically as “the omnibus budget bill,” had increased 12 fold. The advent of the omnibus budget bill did not come about due to an increase in the size of government. Rather, it happened as a function of the concentration of power — in a sense the shrinking of government — especially within the finance department.

The abuse of budgets and their implementing legislation has reached eye-watering level under Finance Minister Jim Flaherty. Flaherty recently introduced his second BIA of this year, Bill C-45. It’s a staggering bill, 443 pages long, amending some 60 statutes. Together with C-38, the government’s first BIA of this year, we have nearly 900 pages of legislation to implement a 500-page budget. A new measure of efficiency in government is thus born.

C-45 is controversial due to the degree of non-budgetary measures it contains, such as amendments to the Fisheries Act, amendments to the Hazardous Materials Information Review Act, changes to the Canada Grain Act, etc. So much so that the minister of finance has now decided to allow various parliamentary committees to study some components of the Bill. This is window dressing of course, because ultimately C-45 will likely be voted on as one gigantic legislative tome.

This year’s budget bills follow on the heels of the 2009 BIA, Bill C-2, which amended more than 40 statutes, many of which had nothing to do with the ways and means of the government. C-2 changed, for example, the Access to Information Act, the Navigable Waters Protection Act, the Canada Council for the Arts Act and the Canadian Race Relations Foundation Act. What are the financial implications of these legislative reforms? There are none. Canadians can be forgiven if they weren’t aware of any of the legislative changes resulting from C-2 because hardly any of them were ever debated in Parliament. C-2 was dealt with as one big omnibus bill, by one little committee of the House — the finance committee — over a few short days.

C-2, C-38 and C-45 are examples of budget legislation on anabolic steroids. This is the way Canada is governed today. It is the tyranny of the finance department. It is the subjugation of Parliament. It is the marginalization of the member of Parliament in the legislative process.

The logical extension of this 15-year path is to have Parliament sit for a week every year and pass with alacrity one big fat omnibus bill that deals with all the business of the federal government for that year. Then our legislators can retreat to their constituencies, we can save a few million tax dollars by turning the lights off early on Parliament Hill, and Canadians can sleep well at night secure in the knowledge that the finance minister and his department has everything in hand.