1. Introduction

Infrastructure is central to every aspect of life in Canada. As a key driver of productivity and growth in a modern economy, as a contributor to the health and well-being of Canadian citizens, as a critical component of transporting goods and services across the country. It is a method for enabling communication and sharing of information between citizens, a means for providing core services such as water, electricity and energy and is a shaper of our how our communities grow and contribute to our collective social fabric.

And, yet, across the country, Canadians are impacted by infrastructure that has failed to be maintained or that remains to be built. This is apparent in the deterioration of our roads and highways, the over-capacity of our public transit systems, underinvestment in affordable housing and social infrastructure, and the increased prevalence of environmental incidents, such as flooding in our urban areas. Canada’s infrastructure, along with the institutional frameworks that fund and finance these assets, are in need of repair.

This paper attempts to set out the need for urgent federal attention to this issue. It will discuss some tools and levers the federal government has at its disposal to engage in what is a national issue, including proposing the creation of a national infrastructure strategy for the country.

This paper will start by reviewing the economic benefits of public infrastructure and highlight how current market conditions create a historic opportunity for increasing infrastructure investment. It will then review current estimates of the size of Canada’s infrastructure deficit, followed by an examination of how the federal government’s role in financing infrastructure has changed over the last 50 years. Finally, it will end by proposing an increased federal role in infrastructure planning and postulate what could be included in a National Infrastructure Plan.

As many have commented before this paper, it should no longer be a question of if we need to devote more resources to public infrastructure or if the federal government should be involved. The question for the Canada at this moment is how the federal government should engage and in what form and capacity.

–

Increasing Focus on Infrastructure:

In recent years, an increasing number of papers have been issued drawing attention to Canada’s infrastructure needs. A select few include:

• Rebuilding Canada: A New Framework for Renewing Canada’s Infrastructure, Mowat Centre, 2014

• The Foundations of a Competitive Canada: The Need for Strategic Infrastructure Investment, Canadian Chamber of Commerce, 2013

• Canada’s Infrastructure Gap: Where It Came From and Why It Will Cost So Much To Close, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, 2013

• At The Intersection: The Case for Sustained and Strategic Public Infrastructure Investment, Canada West Foundation, 2013

• Canadian Infrastructure Report Card, Federation of Canadian Municipalities, 2012

–

2. Economic Benefits of Public Infrastructure

The economic case for investing in infrastructure has never been stronger. In recent years – and particularly in the aftermath of the financial crisis – a consensus regarding the positive economic benefits of stronger infrastructure spending has emerged among economists and policymakers. In addition to the non-economic benefits of infrastructure, a dollar of infrastructure spending has a positive effect on economic conditions in two ways: in the short-term, by supporting jobs and businesses, leading to lower levels of unemployment and higher levels of economic growth; and, in the long-term, by boosting the competitiveness of private businesses, thereby leading to greater wealth creation and higher living standards.

Within Canada, a recent Conference Board of Canada report undertook a detailed examination of the impacts of infrastructure spending on job creation and found that for every $1.0 billion in infrastructure spending, 16,700 jobs were supported for one year1. Moreover, these jobs are not just concentrated in the construction sector, as manufacturing industries, business services, transportation and financial sector employment also benefit from the spillover effect of infrastructure spending.

Increased investment in infrastructure will not only have direct impacts on the economy but will also spread through the economic through a series of multiplier effects 2.

Examining the impact of infrastructure spending on GDP growth has found similar results. The same Conference Board report estimated that for every $1.0 billion in spending, GDP would be boosted by $1.14 billion, resulting in a multiplier effect of 1.143. Other studies have shown similar effects, with estimated multipliers ranging from 1.14 to a high of 1.78, including Finance Canada’s “Seventh Report to Canadians” estimating a multiplier of 1.64.

Critical to this analysis is that virtually all recent estimates estimate the multiplier to be greater than 1.0, implying that every dollar of spending on public infrastructure boosts GDP by more than one dollar. Thus, infrastructure spending generates a positive economic return before projects are even completed, as the construction stage alone generates enough economic activity to justify the expense.

However, the most important economic benefit of public infrastructure is the long-term effect it has on productivity and business competitiveness, which are critical components of a modern, growing economy.

In this case, investments in public infrastructure, such as roads and transportation systems, communication infrastructure, utilities, water and wastewater systems, and health and social infrastructure, result in lowered business costs and increased labour productivity.

Lower business costs result in increased private sector returns, allowing for higher rates of private investment and ensuring Canadian companies can remain competitive and grow on a global stage. Similarly, increased labour productivity results in higher wages and greater wealth creation for Canadian citizens. (See Cost of Inadequate Public Infrastructure for a discussion of the impacts of failing to properly invest in public infrastructure.)

The Conference Board has estimated that roughly a quarter of all productivity growth in recent years is a result of public infrastructure investment5. Similarly, looking over a longer period of time, Statistics Canada estimated that up to half of all productivity growth between 1962 and 2006 can be attributed to investment in public infrastructure6.

Finally, increased economic activity and higher productivity rates allow the government to recoup a portion of its initial investment through higher tax revenues. Although estimates vary, the Conference Board study estimated that governments recover between 30% – 35% of every dollar spent on public infrastructure through higher personal, corporate and indirect taxes7.

Investment in public infrastructure has an immediate, short-term benefit to the economy, while also ensuring that businesses remain competitive in the long run. The alternative is to postpone investment, allowing existing infrastructure to decay and demand for new infrastructure to accumulate, ultimately restricting Canada’s potential for future economic growth.

–

Cost of Inadequate Public Infrastructure:

“The literature shows that inadequate public infrastructure is a threat to long-term economic growth. Inadequate public infrastructure lowers economic potential in a direct and obvious way according to this simple progression:

• Inadequate infrastructure results in increased costs for business.

• Increased costs result in lower return on private investment

• Lower returns—profits—mean less money for business to re-invest in new plants, machinery and technology.

• Less investment means fewer jobs and less productive labour.

• Lower productivity means less economic output and lower personal incomes.

The end result is a loss of competitiveness and lower rates of economic growth.”

At The Intersection: The Case for Sustained and Strategic Public Infrastructure Investment, Canada West Foundation (2013)

–

3. A Window of Opportunity: The Time to Invest is Now

While the general case for investing in public infrastructure is clear, current economic conditions create an even more compelling rationale for investing in infrastructure – right now. Canada is at a unique moment in time where the need for a stimulative macroeconomic policy, historically low long-term interest rates and a large infrastructure deficit, together, combine to dictate the need to accelerate the rate of investment in public infrastructure.

While Canada has fared relatively well compared to its peers, economic recovery from the recent global financial crisis has nonetheless been slow, with employment and GDP growth rates lagging pre-recession levels8. Within this context, an increased focus on reducing fiscal deficits has resulted in a slowing of public spending just when economic conditions could most benefit from increased investment and infrastructure spending.

In a recent paper, David Dodge, former Governor of the Bank of Canada, called on governments to shift emphasis away from short-term deficit reduction to instead “expand their investment in infrastructure while restraining growth in their operating expenditures so as to gradually reduce their public debt-to-GDP ratio.”9 Dodge cites Canada’s lagging productivity growth as a justification for additional infrastructure spending, as increased investment would “enhance multifactor productivity growth and cost competitiveness in the business sector and open up new markets for Canadian exports.”10

In addition, faced with sluggish employment and weak economic growth, and with further monetary stimulus limited by near-zero interest rates11, economists are returning to the idea that targeted fiscal stimulus should be a component of government economic policy. As former United States Treasury Secretary Larry Summers writes:

In an economy with a depressed labor market and monetary policy constrained by the zero bound, there is strong case for a fiscal expansion to boost aggregate demand. The benefits from such a policy greatly exceed traditional estimates of fiscal multipliers, both because increases in demand raise expected inflation, which reduces real interest rates, and because pushing the economy toward full employment will have positive effects on the labor force and productivity that last for a long time12.

According to this recent line of research, traditional benefits of public infrastructure investment are even greater during periods of economic slowdown, as more traditional means of spurring the economy are much less effective. A 2010 paper by Berkeley economists Alan Auerbach and Yuriy Gorodnichenko estimated that the multiplier on government investment is significantly higher (as much as 3.42) in times of recession13. This finding was further supported by a 2012 paper by two economists from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Sylvain Leduc and Daniel Wilson, which focused specifically on public infrastructure spending and found that the multiplier on public infrastructure investment had a lower bound of 3.0 14.

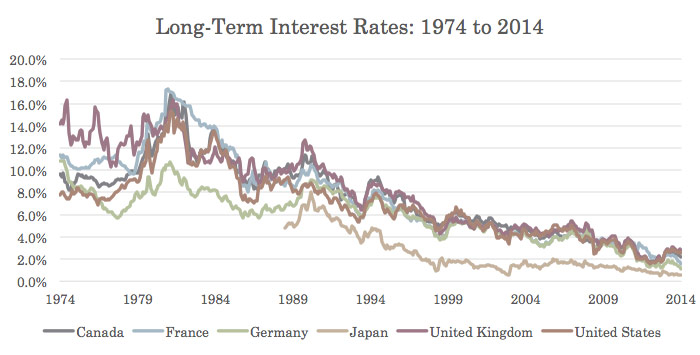

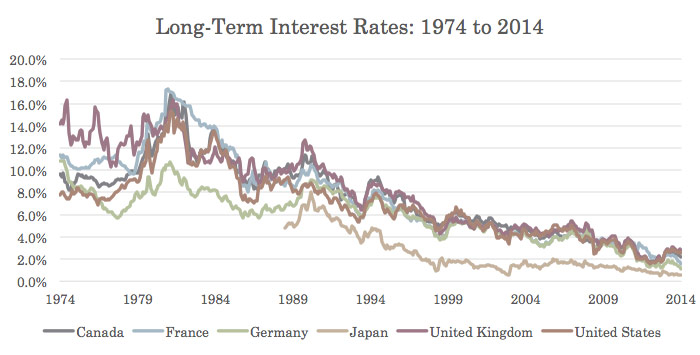

Source: OECD

Finally, historically low long-term interest rates have created market conditions that are ideal for increased infrastructure spending. As can be seen in the above chart, long-term interest rates (that is, government bonds with terms greater than 10 years) have been hovering at levels lower than any point over the past 40 years. Given the long horizon associated with infrastructure assets, long-term, fixed-rate debt financing is an ideal instrument for providing the necessary capital required to increase investment levels. Lower debt-servicing costs effectively reduce the cost of infrastructure investments, while fixed-rate financing insulates projects (and governments) from future increases in interest rates.

These macroeconomic conditions – low interest rates, a sluggish economy, and a looming infrastructure deficit – create a unique window of opportunity for the federal government. Focusing on public infrastructure investment can be a key tool for enhancing economic growth, resulting in increased productivity and employment, and improving the quality of life for Canadians.

4. Canada’s Infrastructure Deficit

Many recent studies have attempted to quantify the current size of Canada’s infrastructure needs. Determining a single number can be problematic, as various studies have focused on specific sectoral needs and have approached the challenge using different methodologies, sometimes resulting in overlap. Thus, instead of trying to determine one figure that represents the size of Canada’s infrastructure deficit, we will briefly review a number of areas that require urgent attention from Canada’s policymakers.

Urban and Municipal Infrastructure:

Since the turn of the century there has been growing interest in urban issues and the role that cities play in securing Canada’s economic competitiveness and high quality of life. Today, municipal infrastructure in Canada has reached a breaking point.

The majority of municipal investment was made when there was little understanding of the role that infrastructure plays in maintaining and strengthening social bonds, public health and the integrity of our natural environment. In many cases, these decisions have locked residents and communities into ways of life that are now perceived as unsustainable. This challenge is magnified by the lack of fiscal levers available to Canadian municipalities as they plan for the future.

Faced with the dual problems of declining investment and aging infrastructure, the Federation of Canadian Municipalities has estimated that Canada’s municipal infrastructure deficit is $123 billion and growing by $2 billion annually15. This estimate is comprised of four categories, including:

- • Water and Wastewater Systems ($31 billion);

- • Transportation ($21.7 billion) and Transit ($22.8 billion);

- • Waste management ($7.7 billion); and

- • Community, Cultural and Social Infrastructure ($40.2 billion).

Moreover, this methodology likely underestimates the size of the municipal infrastructure deficit, as it fails to incorporate other types of infrastructure that are pillars of modern cities and communities. For example, affordable housing and safe shelter, low-carbon energy systems and reliable information and communication technologies help mold municipalities into livable, resilient and economically competitive places.

Road Networks, Transportation and Electricity Infrastructure

Efficient road networks and transportation systems are critical for the functioning of a modern economy. Reducing gridlock ensures that goods can be easily transported across the country, reducing business costs and enhancing trade. Effective public transit and uncongested road networks allow for faster commute times, reducing worker stress and increasing labour productivity.

Within this context, the need for investment has been highlighted by a number of studies:

• The McKinsey Global Institute has estimated that Canada must invest $66 billion into maintaining and repairing urban roads and bridges between 2013 and 2023.16

• Transit systems across the country require $4.2 billion annually for repair and replacement of existing assets. This estimate excludes meeting unmet or future demand.17

• The Canadian Chamber of Commerce has estimated that congestion is costing the country, as a whole, $15 billion per year, which is equivalent to almost one per cent of Canada’s GDP.18

• It is estimated that upgrading Canada’s electricity infrastructure between 2010 and 2030 will cost over $300 billion, requiring an annual investment higher than any level of investment in any previous decade.19

–

Extreme Weather: Too Costly to Ignore

Extreme weather is becoming increasingly more prevalent throughout Canada. The recent spike in natural disasters has resulted in unprecedented social and economic consequences for residents, businesses and governments across Canada. Prior to 1996, only three natural disasters exceeded $500 million in damages (adjusted to 2010 dollars). However, beginning in 1996, Canada has averaged one $500 million or larger, disaster almost every single year.20 And, according to the Insurance Bureau of Canada, for the first time water damage passed fire damage in terms of the amount of insurance claims across the country last year.21

Property damage created by small weather events has also become more frequent. Canada’s sewage systems are often incapable of handling larger volumes of precipitation.22 This is particularly a problem for older cities in central and eastern Canada where there is great need to rehabilitate water and sewage systems to mitigate the chance of flooding. By 2020, it is estimated that almost 60 per cent of Montreal’s water distribution pipes will have reached the end of their service life.23 This is particularly concerning given that the International Panel on Climate Change determines that extreme weather, such as heavy precipitation, will become more frequent over the next 50 years.

The need to prepare for the new reality of extreme weather and climate change becomes clear when the economic consequences are exposed. The average economic cost of a natural disaster is $130 billion and lowers GDP by approximately 2 per cent.24 This is attributable to the rising occurrence of severe weather affecting urban areas that have high-density populations and high-value assets. In the aftermath of a disaster, lost tax revenue and demands for relief and reconstruction place enormous fiscal strain on governments. On average, it is estimated that natural disasters increase public budget deficits by 25 per cent.25

–

Global Estimates:

Finally, a number of global estimates of Canada’s infrastructure deficit – across all sectors and sub-national jurisdictions – do exist. A 2013 study by the Canadian Chamber of Commerce estimated that the breadth of investment needed to address Canada’s infrastructure deficit could be as high as $570 billion.26

Additionally, a recent study by the Canada West Foundation estimated the accumulated infrastructure debt at $123 billion for existing infrastructure, with an additional $110 billion required for new infrastructure.27 Finally, in a sobering report, the Association of Consulting Engineers of Canada estimates that 50 per cent of public infrastructure will reach the end of its service life by 2027.28

Moreover, estimates of the effect of chronic underinvestment in infrastructure have shown that the infrastructure deficit is hindering our national competitiveness. Between the mid-1990s and 2006, infrastructure investment within Canada declined, while the United States increased spending by 24 per cent. During the same period, Canada went from near parity with the productivity of the United States to 20 per cent lower.29

It is clear that, regardless of the exact size of Canada’s infrastructure needs, the various estimates show that the problem is significant in scale and that drastically increased levels of public investment are warranted.

5. Declining Federal Involvement in Infrastructure

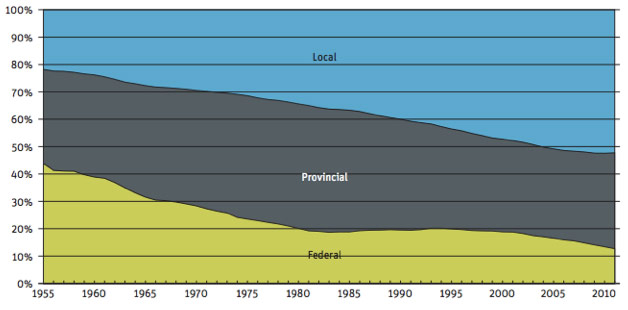

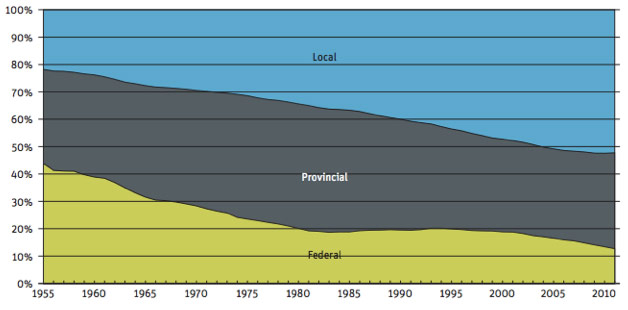

Over the past 50 years, there has been a significant shift in the ownership and funding of public infrastructure between the three levels of government. In 1955, the federal government owned 44 per cent of public infrastructure, the provinces owned 34 per cent and local governments owned 22 per cent.30 Today, provincial, territorial and municipal governments own and maintain roughly 95 per cent of Canada’s public infrastructure.31

Chart 1: Asset Shares by Order of Government

(Canadian Center for Policy Alternatives, 2013)

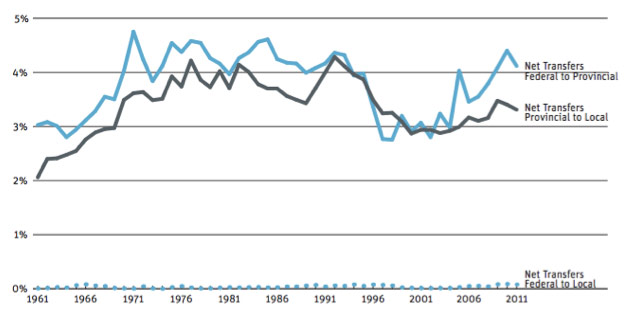

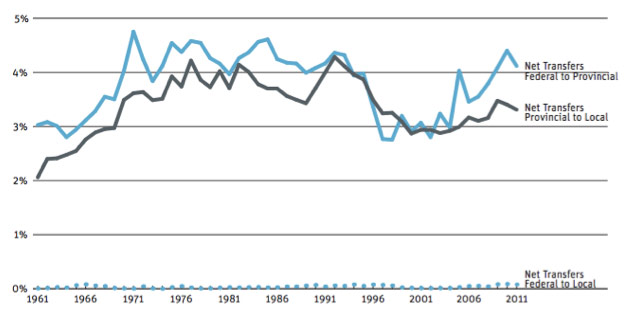

Municipalities own 52 percent of public infrastructure, but collect just eight cents of every tax dollar.32 In our existing taxation structure, the federal and provincial government collect more than 90 per cent of all taxes paid by Canadians.33 Senior levels of governments benefit from sales, income and corporate taxes, which are responsive to economic growth. Local governments are increasingly dependent on property taxes, a regressive funding tool that is the least responsive to growth and impacts middle-and-low-income people the hardest.34 While transfer payments from the federal government to the provincial government increased throughout the 2000s, a corresponding increase in transfer payments from the provincial government to local governments has failed to materialize.35 The shift in responsibilities without corresponding capacity to respond has created a structural imbalance between local authorities and federal and provincial governments.

Chart 2: Intergovernmental Transfer Payments, % of GDP, 1961- 2011

(Centre for Policy Alternatives, 2013)

Recognizing that a new approach to federal funding for provincial, territorial and municipal infrastructure was needed, the Government of Canada began to re-enter the municipal infrastructure conversation in the early 2000’s. This renewed interest led to the creation of the Department of Infrastructure and a series of shared-cost infrastructure programs.

And governments of all political stripes have recognized the importance of infrastructure and have continue to invest. The 2007 Building Canada Plan for example, divided funding between transfer payments and projects that were deemed of national significance. Municipalities would receive $17.6 billion in predictable revenue over the course of seven years derived from the federal gas tax and GST rebate. At the same time, the federal government would invest $13.2 billion in national priority projects.

While we should be encouraged by the interest the past few federal governments have taken in financing infrastructure across the country, according to the OECD our federal government continues to play a relatively small role in funding infrastructure.36 The provincial, territorial and local governments in Canada play a larger role relative to the federal government in public infrastructure funding than is the case in comparative countries like Germany, Australia, the United States and other similar OECD countries.37

The renewed interest in the role and importance of infrastructure saw public investment in Canadian infrastructure reach just over 3 per cent of GDP in 2008.38 This investment barely surpasses the annual investment of 2.9 per cent of national GDP that is required just to maintain the current infrastructure stock.39 By way of comparison, the world average expenditure on public infrastructure is 3.8 of GDP per year.40 To promote prosperity and improved productivity throughout Canada, experts have postulated that a total annual investment of 5.1 per cent of GDP is required.41

While our federal government has shown great progress over the past number of years re-engaging in the infrastructure challenge, clearly there is more work to be done. The next sections lays out the case for a National Infrastructure Plan and its potential components.

6. A National Infrastructure Plan for Canada

Given the national importance of public infrastructure and its critical effect on economic competitiveness and quality of life, it is clear that the federal government needs to assume a leadership role with respect to the coordination and financing of infrastructure within Canada.

In particular, a larger federal role is necessary, and a rebalancing of financing responsibilities is required, for the following reasons:

• Better Alignment of Funding Responsibilities with Fiscal Capacity: As the previous section makes clear, while the federal government’s fiscal capacity is roughly equal to that of all the provinces and territories combined, it contributes only 12% of annual infrastructure expenditures. Municipalities are even worse off, shouldering almost 50% of infrastructure costs, while having the smallest fiscal capacity of all three levels of government.42 To correct this imbalance, the federal government should target a higher level of investment, by both increasing net infrastructure investment levels as well as assuming some of the burden for financing projects that is currently the responsibility of municipalities.

• Aligning Infrastructure Spending with National Macroeconomic Policy: As argued above, fiscal stimulus and, in particular, investment in public infrastructure is an increasingly important tool of macroeconomic policy for national economies. Within Canada, only the federal government has the ability and the responsibility to set economic policy at a national level. As such, to coordinate public infrastructure spending with other macroeconomic tools such as fiscal and monetary policy, the federal government needs to take a stronger role as a coordinator and funder of public infrastructure.

• Increased Investment in Federally-Owned Infrastructure: Certain areas of public infrastructure, such as ports and border crossings, airports, military infrastructure, and national rail and transportation infrastructure, are the sole responsibility of the federal government. Thus, with provinces and municipalities already strained by existing infrastructure demands, only an increase in federal funding will result in higher levels of infrastructure investment in these areas.

• Champion Nationally-Significant Projects: While many areas of infrastructure investment technically fall within areas of provincial jurisdiction, it is nonetheless incumbent upon the federal government to champion – and fund – projects of national significance. Projects such as urban transit and transportation systems, high-speed rail, climate change adaptation, affordable housing and social infrastructure, electricity transmission, and communication systems and rural broadband all touch on national economic priorities, as well as impact the quality of life of all Canadians. While respecting provincial jurisdiction, the federal government should accelerate its rate of investment within these areas.

While recent federal government initiatives such as the 2014 extension of the Building Canada Plan represent a positive step for greater federal involvement in public infrastructure, much more needs to be done to address Canada’s infrastructure deficit.

It is evident that one piece that is missing from the federal landscape is a comprehensive National Infrastructure Plan that could coordinate Canada’s planning and investment decisions with respect to public infrastructure. While a complete, comprehensive plan is beyond the scope of this paper, it is nonetheless instructive to review possible components of what could be included in a National Infrastructure Plan for Canada.

–

UK’s National Infrastructure Plan

In 2010, the UK government introduced its first National Infrastructure Plan.

“…the Government is setting out, for the first time, a broad vision of the infrastructure investment required to underpin the UK’s growth.”

“The role of the Government in this work is clear. It is to specify what infrastructure we need, identify the key barriers to achieving investment and mobilise the resources, both public and private, to make it happen.”43

By 2013, the UK’s NIP, updated annually, included a pipeline of projects valued over £375 billion, status reports on projects valued over £50 million, detailed funding tools and mechanisms, and a comprehensive framework for evaluating and prioritizing infrastructure investment across the country.44

–

What Could a National Infrastructure Plan Look Like?

The need for a National Infrastructure Plan is clear. Countries that exhibit best practices for infrastructure investment have decision-making frameworks driven by a strong central government committed to innovation and economic development. Within these frameworks, projects move forward based on 50 to 100 year forecasting and planning, establishing a platform for innovation, resiliency and prosperity.45

For example, in the Netherlands, the Dutch government has been actively involved in setting strategic infrastructure plans since the 1960’s, particularly with respect to projects of national interest. A recent World Economic Forum report on global competitiveness ranked the Netherlands 1st for quality of port infrastructure and electricity supply and ranks Netherlands 5th overall out of 144 countries in global competitiveness.46

Moreover, national governments are helping cities execute visionary plans that are embedded in infrastructure as a means to enhance global competitiveness. These countries recognize that providing integrated, efficient infrastructure is essential to offering a high quality of life and business environment that prospective investors and residents find attractive and find the means to finance it.47

To help shape this concept, the authors propose that a National Infrastructure Plan could, at minimum, include the following components:

• A comprehensive, multi-year plan that would prioritize infrastructure projects across a number of areas of national significance. This plan would include a pipeline of projects, prioritized by status such as completed, under construction, funded and awaiting approval. Under this structure, the plan would be updated at least once a year to reflect movement in the project pipeline and changes in strategy or emphasis.

• Transparent disclosure of infrastructure planning and project prioritization. Building on the last point, any infrastructure plan would need to transparently describe the infrastructure planning and prioritization process, including publishing decision-making criteria and detailing the status of projects under consideration for funding.

• Dedicated annual targets for infrastructure investment. For example, targeting a certain percentage of GDP each year would ensure that the infrastructure deficit is slowly reduced, while demands for new infrastructure are met. The plan could include flexibility to accelerate planned infrastructure investment in times of economic slowdown or recession.

• A decoupling of infrastructure investment decisions from annual operating budgets. The long-term benefits of public infrastructure investment require a decoupling from the short-term incentives associated with deficit reduction. Although infrastructure spending obviously cannot be undertaken in complete isolation of the government’s fiscal situation and would need to be publicly reported in a transparent manner, it should nonetheless but somewhat insulated from the volatility of annual fiscal budgeting.

• A detailed inventory of infrastructure needs, including maintenance and new build requirements. The federal government should play a coordinating role in collecting and assessing infrastructure needs across Canada. This inventory should then be used by policymakers to prioritize future infrastructure funding levels and project investment decisions.

• Clear, transparent rules for infrastructure funding programs. For programs that involve partnering with provinces or municipalities, application rules should be transparent and predictable. Program funding levels should not be capped, but rather provided with annual allocations, thus ensuring that projects that are unsuccessful in one year can be prioritized in a following year.

• Accounting and budgeting provisions that recognize the multi-year nature of infrastructure investment, including a separate Capital Budget. Again, as infrastructure planning operates on time horizons well beyond annual budgeting cycles, accounting rules and budget planning for infrastructure should be updated to reflect this reality. This should include separately accounting for capital spending within the government’s fiscal budgeting process and ensuring that all infrastructure investments, including projects that are partnerships with provinces or municipalities, are appropriately capitalized over the life of the asset.

• Financial tools for municipalities and public sector entities who cannot efficiently access capital markets. Building on the success of P3 Canada, the federal government should create centres of excellence in financing, access to capital, project planning and infrastructure budgeting that smaller public sector entities can utilize. This centralization of expertise will result in the promotion of best practices across Canada and allow for smaller players to benefit from the economies of scale associated with a pan-Canadian infrastructure plan.

• Dedicated funding mechanisms to address the misalignment of infrastructure responsibilities with fiscal capacity. This could include, among other mechanisms, transferring fiscal capacity from the federal government to municipalities, as the greatest imbalance exists between these two levels of government.

Finally, this list is not an attempt to comprehensively describe what may be included in a National Infrastructure Plan, but rather an attempt to start a dialogue on the subject. The authors invite policymakers and thought leaders to build upon this outline to develop a comprehensive vision for what should be included in a National Infrastructure Plan for Canada.

7. Conclusion

Modern public infrastructure is a crucial component of national prosperity and high living standards. But decades of neglect and underinvestment have left Canada on the precipice of a national crisis in terms of our collective infrastructure needs.

Numerous studies and analyses have shown that Canada faces a substantial infrastructure deficit, both in terms of maintaining our existing assets, as well as servicing unmet demand for new infrastructure. This deficit extends across almost all areas of public infrastructure, including transportation and transit, water and wastewater, social and cultural institutions, affordable housing, electricity transmission, environmental and climate change adaptation and many more. The long decline of federal involvement in infrastructure spending has exacerbated the problem, as the vast majority of infrastructure inventory is in the hands of Canada’s municipalities and provinces, creating a misalignment between funding responsibility and fiscal capacity within the country.

This challenge, while dire, also represents a key opportunity for Canada’s federal government. The economic benefits of investing in public infrastructure are numerous and substantial, with additional investment providing badly-needed stimulative effects in the short-term and contributing to higher productivity and a more competitive economy in the long run. Moreover, current market conditions, including historically low long-term interest rates, create a window of opportunity for decisive action by an active and committed federal government.

It is time for the federal government to play a more active role in the planning and funding of public infrastructure within Canada. A critical starting point would be the creation of a National Infrastructure Plan, following the example of other countries such as the U.K. A national strategy, while respecting provincial and municipal jurisdiction, would coordinate infrastructure efforts across Canada, take advantage of the federal government’s greater fiscal capacity, create clear, transparent rules for infrastructure programs, enhance transparency of infrastructure planning and prioritization and share best practices across Canada. Only the federal government has the ability, authority and fiscal capacity to play this role within Canada.

The state of Canada’s infrastructure represents both a crisis and opportunity for our country. Only by taking decisive action now, can the federal government ensure we collectively seize the latter and avoid the former.

8. Authors

John Brodhead is a former advisor to the Honourable John Godfrey, Minister for Infrastructure and Communities, and a former Deputy Chief of Staff for Policy for Ontario Premier Dalton McGuinty. He was Vice-President of Metrolinx and is now the Executive Director of Evergreen CityWorks, an initiative designed to build better urban infrastructure in Canada. John has a Masters Degree in Political Science from the University of British Columbia.

Jesse Darling is an Urban Project Designer for Evergreen CityWorks. She has previously conducted research and policy analysis for the Martin Prosperity Institute and Harvard Graduate School of Design in urban affairs and municipal governance. She has a Masters degree in Urban Planning from the University of College London.

Sean Mullin is an economist, policy advisor and consultant, and has previously worked in senior roles at the Province of Ontario and in the asset management industry. Sean has a Masters degree in Economics from McGill and an M.B.A. from the University of Oxford.

9. Sources

Canadian Chamber of Commerce (2014): http://www.chamber.ca/advocacy/top-10-barriers-to-competitiveness/Booklet_Top_10_Barriers_2014.pdf

Centre for Policy Alternatives (2013): http://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National%20Office/2013/01/Canada’s%20Infrastructure%20Gap_0.pdf

“Bennett Jones Spring 2014 Economic Outlook”, David A. Dodge, Richard Dion and John M. Weekes (2014): http://www.bennettjones.com/Publications/Updates/Bennett_Jones_Spring_2014_Economic_Outlook/

David Dodge (2014): http://www.cbc.ca/news/business/david-dodge-says-low-rates-should-encourage-infrastructure-spending-1.2673828

Dupuis and Ruffilli (2011): http://www.parl.gc.ca/content/lop/researchpublications/cei-24-e.htm?Param=ce4

Economist Magazine, 28 September, 2013

Environment Canada (2013): http://ec.gc.ca/meteo-weather/default.asp?lang=En&n=3318B51C-1

Federation of Canadian Municipalities (2006): http://www.fcm.ca/Documents/reports/Building_Prosperity_from_the_Ground_Up_Restoring_Muncipal_Fiscal_Balance_EN.pdf

Federation of Canadian Municipalities (2008): http://www.fcm.ca/Documents/reports/Infrastructure_as_Economic_Stimulus_EN.pdf

Federation of Canadian Municipalities (2009): http://www.fcm.ca/Documents/reports/Municipal_Infrastructure_Projects_Key_to_Putting_Canadians_to_Work_EN.pdf

Federation of Canadian Municipalities (2012), State of Canada’s Cities and Communities http://www.fcm.ca/Documents/reports/The_State_of_Canadas_Cities_and_Communities_2012_EN.pdf

Government of Canada (2013): http://www.budget.gc.ca/2013/doc/plan/budget2013-eng.pdf

Infrastructure Canada (2013): http://www.civicinfo.bc.ca/Library/Asset_Management/Presentations/Workshop_on_Asset_Management_October_2013/Federal_Infrastructure_and_Asset_Management–Infrastructure_Canada–October_10_2013.pdf

Insurance Bureau of Canada (2012): http://www.ibc.ca/en/natural_disasters/documents/mcbean_report.pdf

Insurance Bureau of Canada (2014): http://www.ibc.ca/en/natural_disasters/documents/economic_impact_disasters.pdf

KPMG (2012): http://www.kpmg.com/Africa/en/Documents/Infrastructure-100-world-cities-2012.pdf

McKinsey Global Institute (2013): http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/engineering_construction/infrastructure_productivity

Mirza (2007): https://www.fcm.ca/Documents/reports/Danger_Ahead_The_coming_collapse_of_Canadas_municipal_infrastructure_EN.pdf

OECD (2010): http://www.oecd.org/governance/regional-policy/48724540.pdf

OECD (2014): http://www.keepeek.com/Digital-Asset-Management/oecd/economics/economic-policy-reforms-2014_growth-2014-en#page1

PWC (2014): http://www.pwc.com/en_GX/gx/psrc/publications/assets/pwc-investor-ready-cities-v1.pdf

Residential and Civil Construction Alliance of Ontario (2014): http://www.rccao.com/news/files/RCCAO_Ontario-Infrastructure-Investment_July2014-WEB.pdf

“UK National Infrastructure Plan 2010”, HM Treasury, United Kingdom (2010): https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/188329/nip_2010.pdf

“UK National Infrastructure Plan 2013”, HM Treasury, United Kingdom (2013): https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/263159/national_infrastructure_plan_2013.pdf

“Leadership for Tough Times: Alternative Federal Budget Fiscal Stimulus Plan”, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (2009): http://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National_Office_Pubs/2009/Leadership_For_Tough_Times_AFB_Fiscal_Stimulus_Plan.pdf

“Canada’s Economic Action Plan: A Seventh Report to Canadians”, Finance Canada (2011): http://www.fin.gc.ca/pub/report-rapport/2011-7/pdf/ceap-paec-eng.pdf

“Monetary Policy and the Underwhelming Recovery”, Remarks by Carolyn Wilkins, Senior Deputy Governor of the Bank of Canada, September 22, 2014: http://www.bankofcanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/remarks-220914.pdf

“The growth puzzle: Why Canada’s economy is lagging the U.S.”, Globe and Mail, March 5, 2014: http://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/economy/economy-lab/the-growth-puzzle-why-canadas-economy-is-lagging-the-us/article17299527/