Tweet

A few years ago, we began noticing something very different about the way the public looked at the economy[1]. The public seemed to believe that we were encountering an end of progress. The idea of a “better life” or what is known to the south as the American Dream seemed to be slipping away. Among citizens of both Canada and the United States, there was a growing recognition that the middle class bargain of shared prosperity, which had propelled upper North America to pinnacle status in the world economy in the last half of the twentieth century, was unravelling.

In this brief consideration of the political implications of the problems of the middle class, we will examine both perceptions and behaviour (and values). Our work reflects the grand insights of major recent scholarly work by Daron Acemoğlu, Thomas Piketty, Richard Wilkinson, Miles Corak, and others. We believe that this percolating crisis of the middle class is the greatest challenge of our time and we have argued this narrative to very senior audiences in Canada and the United States – whoever will listen and act.

Despite near public consensus on the severity of the issue, and impressive empirical and expert support, many in the media and elsewhere deny the problem. And yes, there is still relative prosperity in the Canadian economy – we certainly aren’t Spain, let alone Greece. The trajectory, however, is clearly to stagnation and decline, except for those at the top of the system.[2]

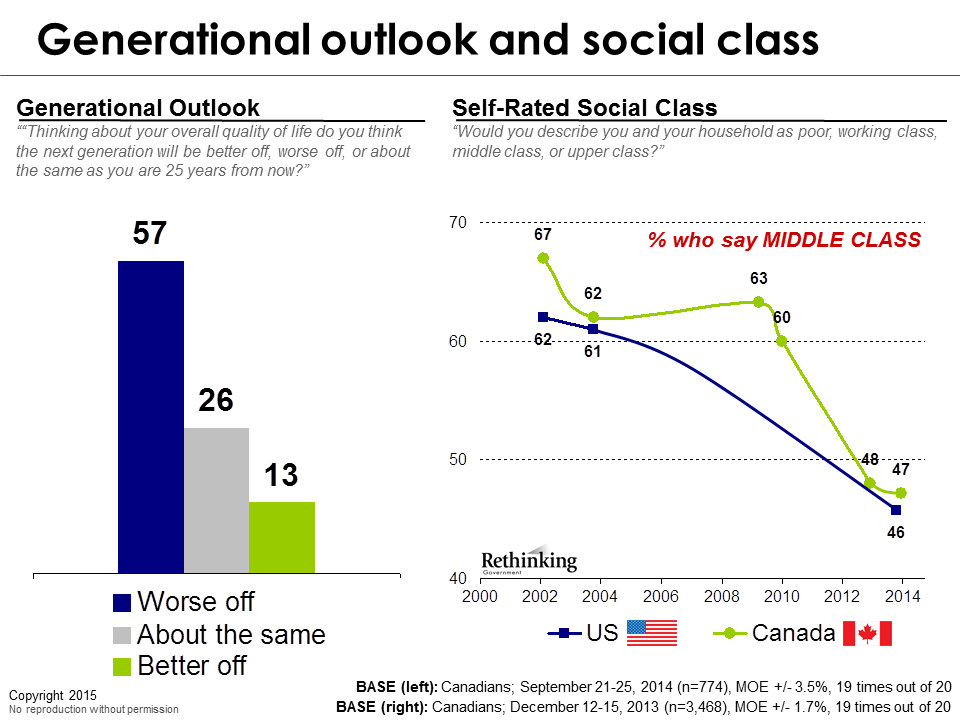

The public are not deluded, nor hysterical. The clarity of public concerns around the issue of middle class decline is remarkable. Moreover, when we unpack this across generational cohorts we can see that the unravelling is much more evident as we move from seniors to young Canada. So while still eminently fixable, the trend lines lead to a very gloomy prognosis which is currently infecting public outlook and threatening to become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Fears are highest when turned to the future, particularly concerns about retirement, and the fate of future generations. Whereas the middle class used to mean one could attain a house and a few luxuries and a better life than one’s parents it is now all about security, which has become the elusive lacuna as it applies to the ability to get by and to retire with security. The grey outlook on the present turns almost black as the public ponder the fate of future generations.

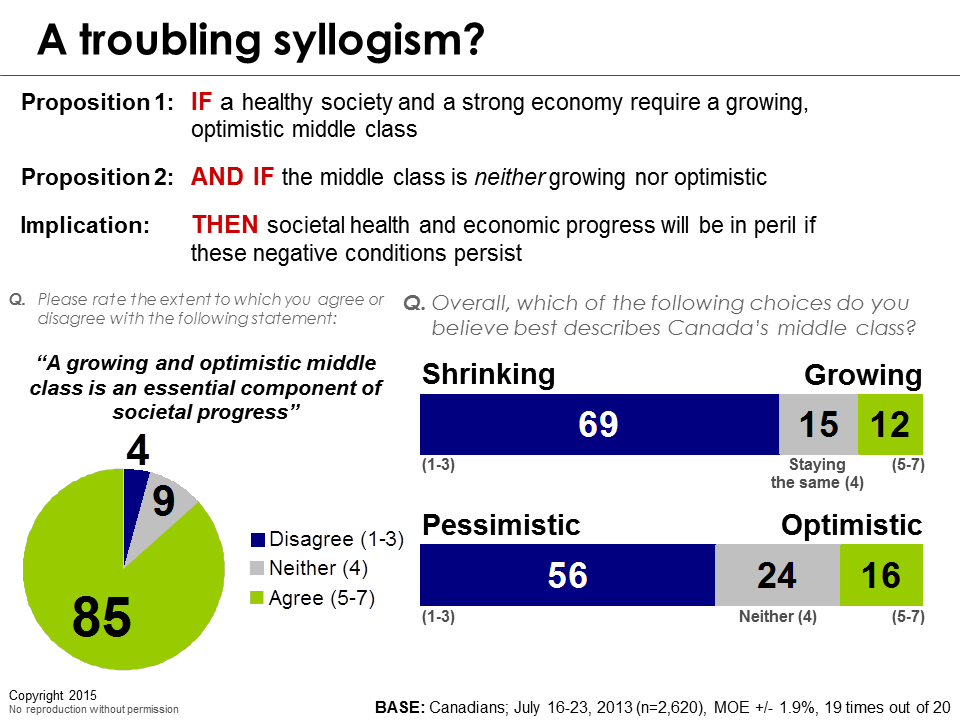

Consider the troubling syllogism laid out below:

There is a virtual consensus that a growing and optimistic middle class is a precondition for societal health and economic prosperity. This consensus position reflects the historical record of when nations succeed.[3] Yet if this consensus is correct, we note with alarm that almost nobody thinks that these conditions are in place in Canada. To the contrary, the consensus view is that the middle class is shrinking and pessimistic.

What has changed?

There are important barometers of confidence and we have tested these the same way in repeated measures for twenty years or so; the trajectories are clear and revealing. Never in our tracking has Canada had such a gloomy outlook on the economic future. Never in our tracking has the sense of progress from the past been so meager. The right wing commentariat may seize upon partial stories/research to suggest: i) this is a non-issue – only of concern to “wonks”; and ii) things are swimmingly well and even if public show fears, they are being foolish. We say the public are right.

The point isn’t that Canada is in a state of privation and economic distress – it clearly isn’t. The point is that the factors that produced progress and success don’t seem to be working in the same way anymore. And the problem is accelerating as we move down the generational ladder.

The current generation sees itself falling backward and sees an even steeper decline in future. The typical optimism of youth is very muted as they encounter an economy that doesn’t seem to offer the same promise of shared progress available to their parents and grandparents.

So it appears that we have at least temporarily reached the end of the progress, the defining achievement of liberal democracy.

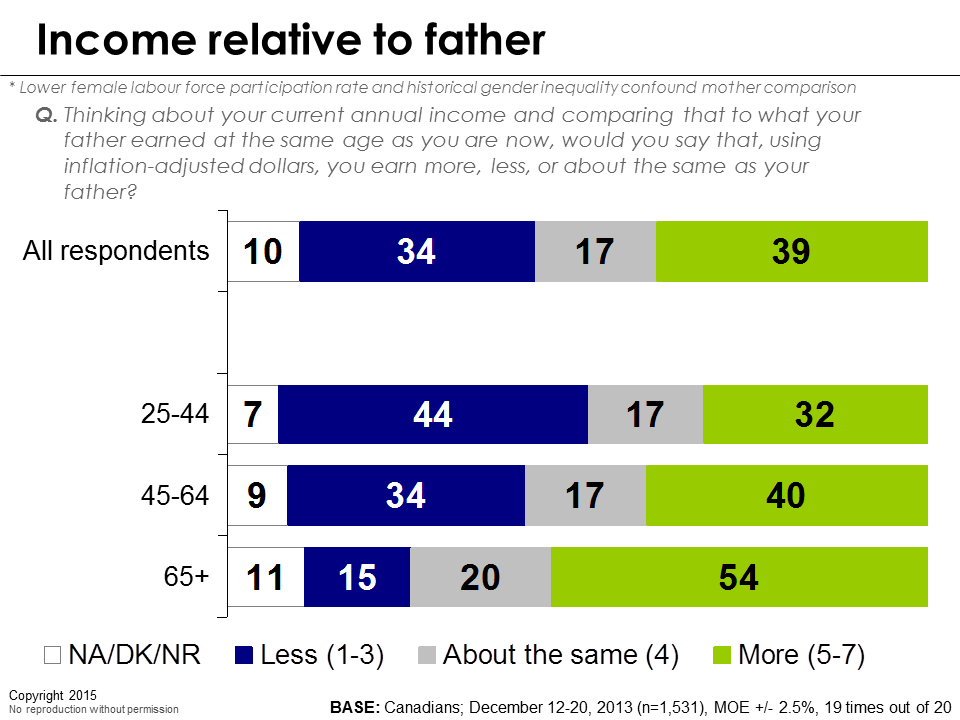

Vertical mobility eroding

The chart above shows a sharp rise in the rate of downward intergenerational mobility as we move from seniors to younger Canada (a nearly threefold increase). Arguably, the prime driver of this is rising inequality which is increasing quickly across all advanced western economies.[4] Notably, as Miles Corak notes,[5] the incidence of upward vertical mobility across generations is dropping most sharply in those places which are becoming more unequal at an even faster pace.

The economic ladder is missing rungs in the middle and people are less motivated to try climbing with those conditions in place. Merit is less relevant as the system is now “stickier” at the top and bottom of the social ladder. This failure of the incentive system is hobbling innovation and effort and creating a more tepid growth pattern where the relatively more slowly growing pie is appropriated by an ever slenderer cohort at the top.[6] We are literally killing the goose that lays the golden eggs underpinning healthy middle class economies.

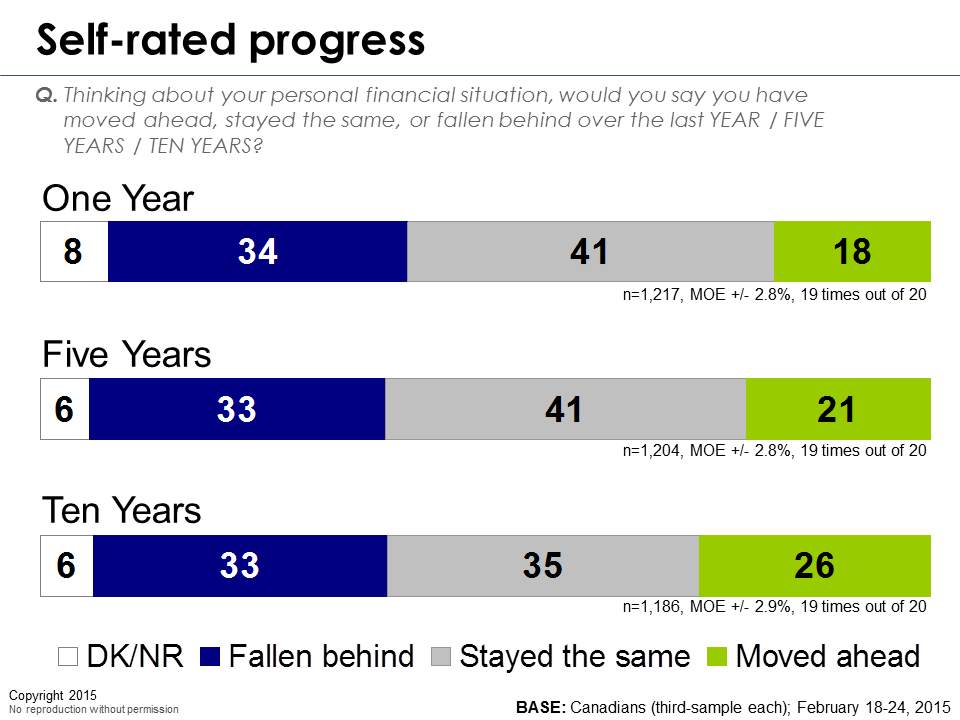

If one thinks this problem is self-correcting or going away, ponder the chart below which is a couple of days old. Very few Canadians think their financial situation is improving but the sense of progress seems to get smaller as we move from ten to five to one year comparisons. What does it say about an economy which defines shared progress as an economic and moral imperative that less than one in five thinks their lot improved last year?

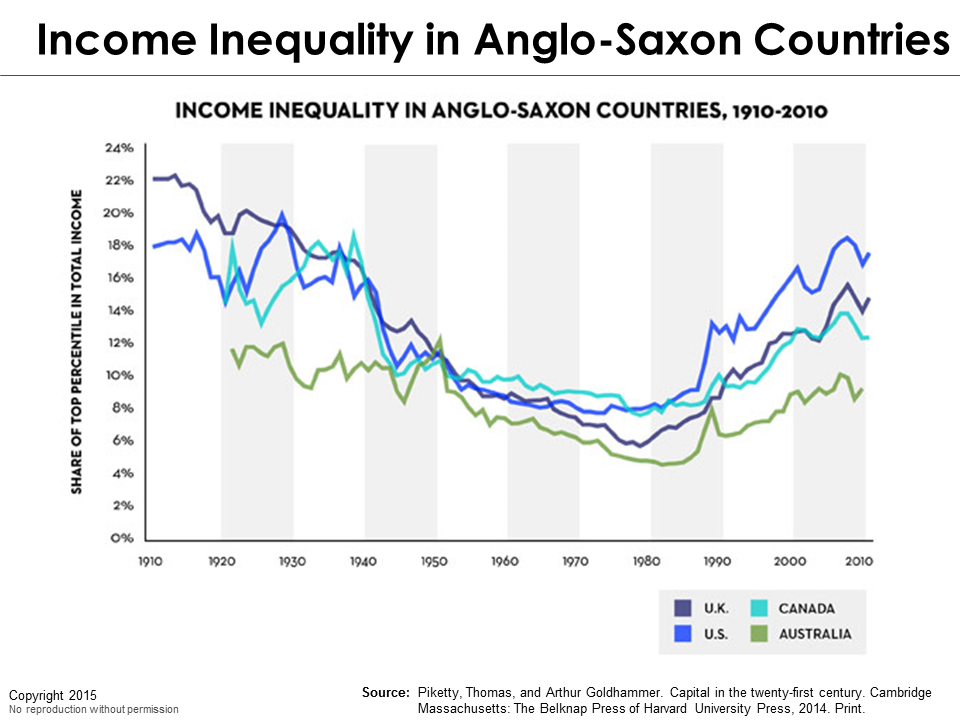

For those who think it has always been like this or that Canada is either immune or charting a differing path, it is not so. In broad brush strokes, four Anglo-Saxon economies have followed the same curve, which seems to be leading to a reproduction of the original gilded age of robber barons which predated the great depression.

Conclusions and going forward

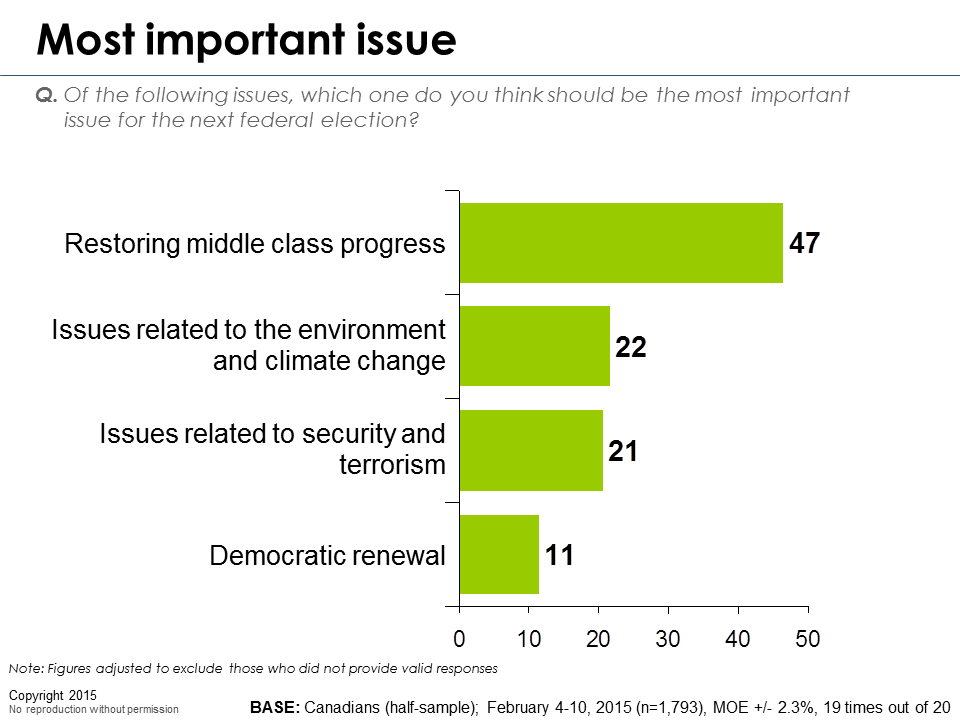

Will the issue of middle class progress be an issue in the coming election? There are good arguments that once the emotion and chauvinism surrounding terror and ‘cultural’ issues fade, this issue will reassume its pinnacle position.[7] What will Canadians think in the fall when the inevitable early enthusiasm for another Middle East adventure doomed to yield disappointment yet again fades? They will look at a relatively moribund Canadian economy lurching along at sub-two-point growth with nothing available for any members of the depleted middle class. They will ponder the prudence of a long term bet on the short term prospect for carbon super power status. They will look enviously at an American economy moving at twice the clip of ours under the explicit framing of what Obama calls ‘middle class economics”. They will look to their prospective leaders and ask who has the most plausible blueprint to restart middle class progress?

Tweet