Tweet

There are a little more than 4 million children in Canada aged 0 to 12 years.[1] They need care and education. I don’t think anyone really disputes this–youth 13 and older obviously also have needs for care and education but they’re not the focus of this post. In most cases, decisions about that care and education are made by parents or legal guardians who will have the bests interests of their children at heart. I don’t think anyone disputes this either. Those children and the families making decisions for them are really, really diverse. So why do we keep trying to produce national public policies on child-care that are one-size solutions?

Sometimes one-size fits all means everyone gets the same kind of choices for childcare.

Supply-side solutions look for ways to increase the number of spaces for children in quality childcare programs. For example, Quebec’s provincial childcare system provides all families with a regulated space in a childcare centre or in licensed homecare and regulates the out-of-pocket costs to parents. In a long-overdue move the province has started to tie that fee to household income. The 2005 federal-provincial agreement on childcare was similarly intended to increase the supply of regulated spaces in the rest of the country. All provinces in the country provide some financial support (from some combination of federal transfers and their own tax revenues) for the early learning and care services in their jurisdiction. In 2006-07, there was also a short-lived federal effort to look for recommendations to encourage employers to create more childcare spaces for their employees. That last effort ended quietly.

It’s not totally clear we have a supply-side problem when it comes to learning and care for kids. Our indicators on the supply of childcare in Canada are a bit problematic in that they exclude other options used by families like after-school recreational programs and homecare with too few clients to require a license.[2] What we do know is that there were 585,274 licensed spaces (in centres or licensed homecare) across Canada (outside Quebec), which makes it sound like as many as 85% of kids are going without childcare from infancy to middle school. In reality, we have to adjust that ratio to account for other factors like access to parental leave, private care arrangements and programs that may be high quality and developmental but fall outside provincial regulation. Furthermore, depending on the age of the child, between 40 and 60%[3] of families say they don’t use any daycare services (note the switch here to “daycare”) at all. How do they manage? Well, probably through some combination of private arrangements, adjusting their work hours and relying on things like full-day kindergarten (where they can) and after-school recreational programs. When parents are asked what matters most to them when they choose their childcare, parents report that location, trust in the provider and affordability are, in descending order, their 3 primary criteria with location by far the most frequently-cited factor.[4] So, getting the supply-side right has to mean attention to a really wide range of types of care, the market price of that care and even the minutiae of where that care is physically located. That’s a tall order if you want to rely on just one policy instrument, no matter what that one instrument is.

Sometimes, one-size fits all means giving everyone the same financial support, regardless of need or ability to pay. This is when really strange things can happen.

Demand-side solutions look for ways to reduce the need for childcare or to subsidize the market price of that care. For example, all provinces outside of Quebec offer income-tested subsidies for licensed childcare services. Quebec did away with subsidies when it introduced its universal daycare plan which has led to an interesting puzzle: Among households who say they use childcare, Quebec households are more likely to say they pay $10 a day or less, but modest income households (making under $40,000/year) are significantly more likely to say they pay $0 out-of-pocket for that care if they live outside Quebec than inside Quebec.[5] In short, swapping subsidies for flat fees seems to mean that costs for childcare are lower on average across all households but are actually higher for lower income households.

Federally, there are two key instruments intended to help families with the costs of childcare. The Child Care Expenses Deduction (CCED) lets parents deduct eligible out of pocket childcare costs, within certain limits. It was recently increased to $8,000 for each child under age 7 starting in the 2015 tax year. When the 2005 federal-provincial supply-side agreement on childcare was cancelled, the money was used to create a new flat cash transfer of $100 per month for each child under 6 years–the Universal Child Care Benefit (UCCB). Financing the UCCB also meant diverting money out of the income-tested Canada Child Tax Benefit system.[6] The UCCB was recently expanded so each child under 6 creates a flat entitlement to $160 per month and each child aged 6 to 18 years generates flat entitlement to $60.

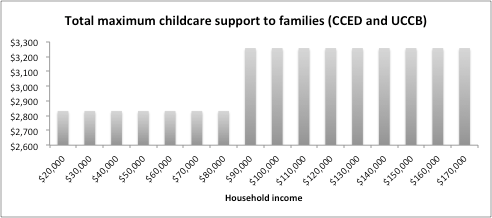

The CCED and the UCCB are both responsive to parental income in some weird ways. The CCED has to be claimed by a working (or student) parent with the lower income and the UCCB is taxable in the hands of the lower income parent (regardless of their labour force activity). Let’s take a simple case, where two parents in a household have equal incomes, or at least incomes in the same federal tax bracket. Figure 1 (below) shows the maximum federal benefit they could receive out of the CCED and UCCB for one child under 7 years of age in the 2015 tax year.

The net effect is that direct federal demand-side support generally rises with household income. The UCCB purposefully pays the same amount, before taxes, no matter a household’s actual expenditure on learning and care. The CCED lets families claim some tax relief only after they’ve spent the money on eligible forms of daycare–an approach that works far better if a family can afford the cashflow pressures in the interim and has enough tax liability get some real benefit out of a deduction.

Policy proposals that promise the same amount of money to all families, whether they are supply-side or demand-side solutions, are politically attractive. They make for nice pithy bumper-sticker commitments that are easy to communicate. But they come with real problems because neither is able to adjust to the needs and means of Canada’s diverse families. In either case, some strange things seem to happen.

Maybe the primary problem in the current childcare policy debate is that it has pitted families who use daycare against families who don’t. Families who use daycare are reduced to supporting a one-sized supply-side approach. Families who don’t are reduced to supporting equally one-sized demand-side option instead. In neither case does the debate acknowledge or respond to a more realistic range of preferences, needs and ability to pay.

What if instead, our starting point was that:

- Childcare is what all families provide for their kids.

- All of those kids need learning and care.

- Many, but not all families meet their kids’ needs for learning and care through daycare.

- Different families will have different demands for early learning and care in their community.

- Different families will have different abilities to pay and out of pocket costs.

There are lots of different levers that could be used on the family policy front and it’s time they started to be used in more nuanced, integrated ways. This route doesn’t lead to simple policy solutions of $X per day or $X per month. Maybe we’ll just have to start making some bigger bumper-stickers.

Tweet

Jennifer Robson is an Assistant Professor at Carleton’s School of Political Management. Contact her at jennifer.robson[at]carleton.ca